What I’d Do If I Became Ironman CEO…

Having noticed the Ironman Corporation is looking for a new CEO, I decided to record an episode sharing what I would do if I were tasked with the job.

This is of particular interest to me as I attended the 1989 Hawaii Ironman World Championships, which used to be held annually in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. My time of 8:57 is still the USA record for the 24 and under age group, so I haven’t had to return (thank goodness!), but it’s great to see how triathlon has grown like crazy since my days on the pro circuit (’86-’94), not to mention endurance sports in general. However, some of this growth has come at a cost to health and well-being, and there have been many complaints about over-commercialization and the extreme costs of competing. As you’ll hear during this show, there are a few specific things that I would do to improve the Ironman experience and make it more accessible for a wider group of people. Yes, Ironman, like all corporations, has a right to make a profit, however what about students or people who cannot afford the expense of competitions like Ironman?

From aerobars to road cycling to drug tests, there are many improvements that could be made to this competition, so if you are an endurance athlete who wants to know what those potential improvements are, this is the episode for you.

TIMESTAMPS:

Much is changing in the world of triathlon. They are looking for a new CEO for the Ironman corporation. [00:24]

Brad shares his experience of putting on several events himself. His take on the increases of entry fees seems fair. [05:18]

If Brad were the CEO of the Ironman corporation, he would make the distance shorter. [10:30]

The Ironman was started in 1978 by a bunch of drunken sailors coming up with random distances. Why is it held in such high esteem when it actually compromises the athlete’s health? [11:46]

People with tattoo of Ironman on their body should get paid as a sponsor. [17:25]

AS CEO, Brad would ban Aero Bars for recreational athletes along with banning road cycling. [19:04]

Drug testing is controversial, especially for amateurs. [30:05]

LINKS:

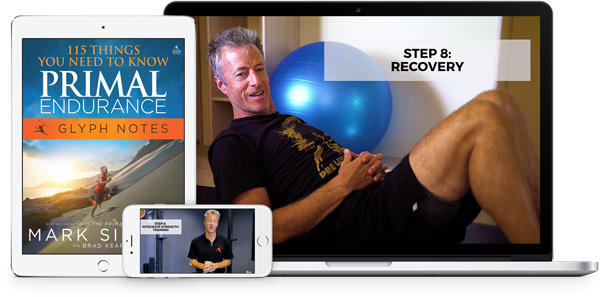

- Primal Endurance Mastery course (FREE bag of Whey Protein Superfuel if you sign up for the full course, just email us!)

- Brad Kearns.com

- Brad’s Shopping page

- PrimalEndrance.fit

- B.rad Whey Protein Isolate Superfuel (Now Available in Cocoa Bean)

TRANSCRIPT:

Brad (00:00):

Welcome to the Return of the Primal Endurance Podcast. This is your host, Brad Kearns, and we are going on a journey to a kinder, gentler, smarter, more fun, more effective way to train for ambitious endurance goals. Visit Primal endurance.fit to join the community and enroll in our free video course.

Brad (00:24):

Hello, primal Endurance podcast listener. I’m sorry that we have not had a regular aggressive publication of episodes. I direct you over to my B.rad podcast where we are on schedule with a couple great shows a week about a broader subject matter of diet, exercise, health, fitness, peak performance, relationships, happiness, longevity, and many things of interest to the devoted endurance athlete. But it’s great to see that we still have some really impressive download numbers, people going back into the archives and tapping into the many wonderful interviews I’ve done on this show with the greatest athletes, coaches, endurance experts, authors, and I’m glad you can go back there and explore the archives, and I will be committed to publishing updated shows regularly and keep the dream alive. Primal endurance. Anyway, today I wanted to have a little fun and riff on a topic that popped into my head when I saw the news that the Ironman Corporation was looking for a new CEO and they’re doing a pretty sophisticated search.

Brad (01:38):

’cause someone sent me this confidential notice with all the parameters like a job hunt, a headhunt, and it’s also in mainstream news channels. So, what’s interesting to me is reflecting on my beginnings at the inception of the professional aspect of the sport back in the mid eighties, and how much the sport has grown today, to the point where there’s a corporation that’s now a billion dollar revenue company with 600 employees and 235 official Ironman branded events around the world each year. Back in the eighties, there was one Ironman every year. It was in Kailua Kona, Hawaii. It’s been held there annually until 2023 for the first time ever. Oh, no, excuse me, with COVID. They had to cancel it. And they, they put the Ironman World Championships in St. George, Utah, but they also decided to hold the Men’s Ironman World Championship race in Nice, France this year, which is the location of another fantastic race, one of my favorite ones ever.

Brad (02:43):

It was called the World Long Distance Championships, held annually in Nice, France in the eighties and nineties and and into the two thousands. So, they’re now, uh, going away from the epicenter of Hawaii, with some other, options and branching out. I think some people are, uh, pretty upset about that. Uh, but the problem is so many people wanna race in the world championships that they simply can’t hold, uh, that number of athletes in the small town of Kailu, Kona. So what they did was they had the men’s race in Nice and the women’s race this year in Kailua Kona. Boy, one of my favorite places, the big island, love that town. And what I especially love now is going back there and not having to race the Ironman, ’cause my quote unquote vacations over to Hawaii. In the old days to participate wasn’t really much of a vacation.

Brad (03:37):

You sit around in your air conditioned room, conserve energy, maybe go out and do a workout and test things out, and then you go slam yourself for a full day out on the lava fields. And, I do get some PTSD flashbacks when I’m out there, uh, shopping at the farmer’s market, and I get overheated and have to go sit down in the shade. And I think to myself, what the heck was I thinking? What was I doing here at 2:00 PM in the afternoon when I’m getting overheated at the farmer’s market, buying papayas and mangoes where I used to be racking my bike and hitting out to run a marathon in that oppressive heat that you get on the Kona Coast? So, my time, 8:57 back in 1989 was a record in the, uh, 24 and under division and still holds 33 years later.

Brad (04:24):

So I do not have to go back and participate, thankfully, I can just keep, keep jawin’ about that from the sidelines. So speaking of this, uh, CEO search, um, I want to take the opportunity in this show to tell you what I would do if they forced me to become CEO of the Ironman Corporation. And, there’s some controversy in complaining about this commercialization of the sport and having a billion dollar company, you know, focused on revenue and sponsors and perhaps marginalizing the athletes at times or the needs of the athletes. And one of the things you hear complaining about is the continued escalation, uh, in the, uh, entry fees for the race. And I’m gonna push back on this a little bit because after I competed as a professional, I became a race director for about 10 years.

Brad (05:18):

I put on what I called the world’s Toughest Half Ironman triathlon in Auburn, California. And boy, it was an unbelievable massive amount of work. It was clearly the most overwhelming and stressful career challenge I’ve ever had by far compared to sitting down and writing a book, which can also be stressful and difficult. But there was nothing like putting on a major event with up to 725 athletes and all the logistics and the multitasking in the plate spinning, and my phone ringing off the hook and my email box blowing up for at least the last week of the race was just nonstop gas pedal on the floor, working 18 to 20 hours a day the night before the race, I’m staying up marking the course and doing things that you have to do in the middle of the night so there’s no disruption and no one knocking over your cones.

Brad (06:08):

So I’d stay up until about 3:30 or 3:45 marking the course, and then my alarm would ring at four 15 to get up and get down there to the swim start in time for all the preparations before a 7:00 AM swim start. It was absolutely mind blowing how difficult it is to be a race to race director. And I must admit now that when I finished racing, I figured that I would be an expert race director by virtue of participating in around 130 triathlons around the world and having this vast database of knowledge from being an athlete at the front of the pack. And oh my gosh, the first weekend of my first race, I realized that I knew f all about how to organize a team and, uh, you know, a staff of, uh, 15 or 20 and a volunteer base of around 120 to 150 for my race in particular.

Brad (06:58):

And boy, I was just in over my head right away. And even after a decade of experience, it was no easier or only slightly marginally easier than that first time. So the reason I’m giving you this background is that I definitely advocate for the race directors to make a fair profit and perhaps even a handsome profit in the case of a corporation like Ironman. And in the case of the many mom and pop race directors who might, uh, organize one or two or eight or 12 races a year, it’s an amazing, uh, gesture to the community to present the competitive venue, especially when it’s out on public roads. And you’re dealing with public agencies and going to meetings for months in advance to get the permission to close down the state park running trails that day, or hire the California Highway Patrol, in my case, to close down five or six major intersections for many hours so the race could happen.

Brad (07:56):

There’s so many logistics behind the scenes, and largely the highly focused, driven, competitive athlete who shows up and demands everything to be perfect. And if something is not perfect, they will sound off on the forums and message boards of triathlon and your race will have a, a black mark against it, and the rumors will spread. So it was a very, very demanding audience, and I think, uh, not enough empathy for what it’s like on the other side. So having been on both sides, I’m gonna say give race directors a break, uh, put the screws to them when necessary because if they sacrifice your safety in the name of profit, or it looks a little, uh, a little, a little like, uh, the commercialization aspect was perhaps more important and more attention to detail where the sponsor banners went versus the attention to detail how well the course is marked.

Brad (08:45):

Yes, they deserve some heat when they’re overlooking the needs of the athletes, especially the safety. And I am proud of the safety record that we had at my events because strongly influenced by my background, especially as an elite racer, racing at the front of the pack. Because if you have a dangerous intersection that’s poorly marked or poorly controlled, guess who is gonna be the most vulnerable? That’s right, the first guy to show up at that crazy intersection where there’s not enough cops, or they’re not doing their job aggressively enough. So I went to great lengths to make sure that the course was marked beautifully, having gone off course on a few occasions in my career and lost prize money accordingly, because the marking was terrible. And that was always my priority. and again, trying to make a fair profit for, uh, doing this, as a business venture.

Brad (09:35):

So if your entry fee has gone up in Ironman, I don’t know what it is now, is it hundreds of dollars, $800 or $600 or a thousand dollars? Whatever it is, it’s probably a deserved entry fee for the experience that you’re getting and the effort that it takes behind that. So there. That’s my, that’s my take on entry fees. However, uh, I always had a policy in my events for a fixed income or full-time student could appeal and send an email and say, I hereby request a lower entry fee due to my circumstances, and we would always honor those people because we do not want to turn away anybody for budget reasons, especially when you’re talking about a sport that’s so massively expensive to participate in anyway, where you have to, you’re kind of obligated if you wanna be competitive to buy the $450 wetsuit and the $8,000 bike, and now I guess the $400 running shoes, right?

Brad (10:30):

And, there you go with the entry fee on top of that. Okay, so as CEO of the Ironman, I’m taking over for a day. Uh, I’m not going to, cow tow to the need to dramatically reduce entry fees because the entities are making too much profit. Let’s sit on that one. But I will object to the my main contention here with the commercialization of endurance sports is the romanticizing of extreme endurance challenges that are almost certainly unhealthy for most people. So if I were CEO day one, my first act upon taking helm would be to cut the Ironman distance in half. So that hereby heretofor, the Ironman is 70.3 miles. It’s still an incredibly long extreme endurance achievement to swim 1.2 miles in open water, bicycle 56 miles and run 13.1 miles. But for the vast majority of participants, I’m not talking about the pros who are training 5, 6, 7, 8 hours a day and are highly competent and are racing the Ironman all the way through to the finish for 140 miles.

Brad (11:46):

I’m talking about the mass participation. So perhaps we could keep the professional championship events at the traditional Ironman distance, but for most of us, I think we should down downshift and downsize our ambitions. Because remember, the Ironman distance, has been glorified by marketing hype. And it started as a whim and a folly where a bunch of drunken sailors were sitting around in Honolulu debating, which was the toughest endurance event in the Hawaiian Islands. And the three up for, uh, consideration were the Waikiki rough water swim, 2.4 miles, the bicycle ride around Oahu, which was 112 miles on that organized bicycle ride, or the Honolulu Marathon, of course, 26.2 miles. And then some wise guy might’ve been John Collins, who’s credited with creating the event, said, Hey, why don’t we try to do all three in a day and then we’ll certainly be an Ironman.

Brad (12:39):

And that in 1978 was how the race started. And so these are random distances that were stacked together as a fun endeavor one day many years ago. And now it has become, supposedly the ultimate athletic achievement in multi-sport is to complete an Ironman. And so when you’re walking around, uh, joining this triathlon community at whatever level you started at, the talk will always escalate to, oh, do you aspire to do an Ironman someday? Have you ever done an Ironman? Well, no, I just do sprint triathlons. I’ve only done Olympic distance. Well, I’ve done a couple of halves, but never a full, that’s the kind of talk and the mentality that’s been programmed into our brains as endurance athletes to celebrate the longest race as the most esteemed accomplishment. And I’m gonna call BS on that for a moment, because wouldn’t it be an awesome athletic accomplishment to go out there, even at a sprint distance triathlon, and really excel and push your body to that anaerobic threshold red line, and have a really fast, strong swim where you beat your time from the previous, and then get on that bike and actually pound the pedals and hammer like the, the glorified athletes in the Tour de France do, and then get off that bike.

Brad (13:58):

And rather than shuffling and dragging your feet all day through an Ironman where you’re barely going faster than a walker, in many cases, a lot of the population in the race is walking rather than running. So it’s not a 26.2 marathon run. It should be called a long ass shuffle slash walk slash a little bit of jogging while your family and friends are waiting patiently for 13 or 14 or 15 hours for you to finish. What if Ironman were 70.3? I think the world would be a better place. And I know this is a super controversial take. I already popped off a little bit on social media and got some choice comebacks like, Hey, it is an always will be the ultimate triathlon. Yes. And that is because of marketing hype and profit seeking enterprises luring you to the starting line to pull the trigger and sign up and make the commitment to prepare for such an extreme event.

Brad (14:53):

But when you overlay someone who’s living an ordinary, normal life with family and work responsibilities and a social life, it can easily overwhelm your life to the extent that the entire endeavor compromises your health in pursuit of peak athletic accomplishment. And I’m not in favor of athletic events that compromise your health. Uh, if you’re getting a little chapped at Brad riffing on all this, remember, I’m coming from the perspective that I spent nine years of my life competing on the pro circuit and training my butt off to make those incremental gains in fitness and performance so I could rise up the finishing, list from seventh to fifth to perhaps a victory. And all of that compromised my health significantly for the entire time, the entire duration of my professional career, my health was on edge or over the edge while I was continuing to refine my fitness.

Brad (15:54):

And today, I am so happy to report, and I have so much content on both this channel and the B Rad podcast about how I’ve transitioned my athletic goals into the sprint power explosive category because they’re alluring and appealing and new for me. So I want to be good at sprinting and high jumping and speed golf, which is a relatively shorter duration, but still an endurance event where you’re running for 45 minutes. Uh, but I feel like these endeavors are more aligned with health and less destructive to my health than the extreme endurance training required to excel at the highest level on the professional circuit, even at short distance events, of course. And for the recreational triathlete, the extremely long distances that you’re training for are going to come at the expense of your health just because of the hour, the time count, as well as just the, the overall training and stress load piled onto all the other forms of stress in your life.

Brad (16:53):

So there’s my pitch and there’s my declaration that Ironman is cut in half. And if I were a CEO of USA, track and field road running department, I would do the same for the fricking marathon. Yes, we can still watch the, uh, the elite performers, uh, try to break two hours and enjoy being spectators on the sidelines after we complete our 13.1 mile ordinary human marathon. Okay, cutting distances in half.

Brad (17:25):

Next item on the agenda, first day as CEO are reparations for everyone who is currently sporting the Ironman logo as a tattoo on their body. So it’s been for many years, decades a rite of passage and a common practice to finish your, perhaps your first Ironman race and then go get a tattoo. The favorite spot is on the side of the hip where the tattoo is visible, clearly when you’re wearing a speedo, as you often do when you’re training and doing swim workouts, uh, or perhaps visible through the split when you’re wearing split running shorts for your running workout.

Brad (18:03):

But it’s kind of like the key location for the Ironman tattoo, where they call it an m.tattoo because the logo is an m with an i with a dotted I in the middle so that the middle stem looks like an I. So here’s the thing. Uh, someone paying good money to the tattoo artist to wear a corporate logo, I think should be compensated, uh, for that wonderful sponsorship and endorsement of the brand. And so rather than, I mean, we gotta pay the tattoo artist, right? But the Ironman Corporation, you send me a picture of your m tattoo that you’re sporting around every day around other athletes, and I’m gonna pay you a sponsorship fee. How about that? Okay. Um, I mean, look, I’m certainly willing to put a corporate logo tattoo on my body after a great athletic achievement, if that’s the occasion. But they’re gonna have to pay me a million bucks. So if you wanna swoosh on the side of my arm or three stripes or whatever the logo is pay up and that’s what’s fair.

Brad (19:04):

Alright, next, I’m going to ban Aero Bars. This coming from the first multi-sport athlete ever to use Aero Bars. in a multi-sport event. That was the Desert Princess Run Bike Run back in February of 87. I busted them out secretly. I actually got them shipped to me from the inventor of the DH bar, uh, Boone Lennon up at Scott USA. I got it like on a Wednesday, I put ’em on my bike and I rode around for five miles, testing ’em out. Then I rode again, maybe 15 miles, and then it was time for the race. And so I showed up in the morning and put this bike and the bike racks, if you could imagine, with these crazy looking aerodynamic handlebars.

Brad (19:44):

And people were laughing and smirking and saying, what the heck’s that? And then, uh, just as the race went that day, it was a run bike run. So first race was a 10 K run, 38 mile bike through the desert, uh, finishing with the 10 K Run. It was the World Championship, Desert Princess series. And I had a, a slower run at at, at the start. A lot of guys went out too fast as they’re known to do in that race. And I believe I was like, 24th after the first run. And I ended the bike ride, tied for third and fourth. And so I passed a bunch of top pros in the world in this aerodynamic position, and everybody I passed looked at me with complete shock and stared at this position. And you could see it registering in their brain that, oh my gosh, this is a vastly superior position than trying to hunch over the regular handlebars.

Brad (20:33):

And it’s been a sensation in triathlon since that day. And of course, the aerodynamic handlebars provide a significant advantage, probably the most dramatic you can go look up on YouTube. Greg Lamond, the Tour de France 1989 when he came from behind in the final time trial and won the tour. Remember, a three week tour lasting for dozens of hours. He won by, I believe, eight seconds over at La Finon due to his sensational final time trial where he busted out the aerodynamic handlebar for the first time ever in the Tour to France. The traditionalists were just, against it. And when they saw Lamond going at 34 miles an hour for that short time trial around Paris, um, they very quickly made their way into the ranks of professional cycling. Uh, but anyway, that’s a little bit of history for the aero bars.

Brad (21:20):

And one thing that occurs to me today is that, again, when we’re talking about recreational athletes who are just going out there trying to have a good time and finish, um, the Aero Bars.are significantly, slightly to significantly more dangerous when you’re out there on the road training with them. So I would ban them in the amateur categories. Sorry guys. I know it’s more fun to pick up a mile per hour or two, but when you’re on the open roads and training in traffic and get ready for the next one, I’m gonna slap you with, um, they have I think some, a significant compromising in your ability to handle the bike when you’re stretched out into that position rather than the traditional drop handlebars where you’re holding on and you’re sitting up a little more upright where you can navigate obstacles, navigate traffic a little better.

Brad (22:07):

So the guy who started the Aero Bars. scene in multi-sport is now gonna ban him, uh, as CEO. And guess what else I’m gonna ban? I’m gonna ban road cycling. So, uh, here, from here on in, uh, all triathlons must take place on dirt roads or paved bicycle pass. And I do not want athletes out there training on these super expensive road bikes out on the open road. Here’s the thing, you are risking your life every single time you set out for a routine training ride, especially in the modern days where we have the ubiquitous mobile device in hand, including with a lot of drivers. And we also have giant SUVs. So fortunately, I put in my miles out on the road now it’s been 25 years since I’d been out there, so there weren’t any people doing text messaging while they were driving, and they didn’t even have the giant SUVs back then.

Brad (23:03):

And so I feel like it was a lot safer, less distracted driving, but still, you know, think about it. You probably have a family loved ones. You love your sport, you love the diversion of breaking free from the office or home life and getting out there on the open road and pedaling. But when you set out, as soon as you leave your driveway and go onto the public street, you are doing almost certainly the single most dangerous thing that you do in life. Buy a factor of 10 x or 100 x. Quick, get on a notepad. Write down the 10 most dangerous things that you do in a routine daily life. Uh, okay, if you’re a professional tree faller, like the guys that I see climbing up 80 feet onto palm trees, cutting down the fronds and then jumping over to the next tree while they’re cabled in that seems a little dangerous.

Brad (24:02):

It’s also dangerous to be a coal miner. There are also other careers that are super dangerous inherently, and those people are taking those risks. But for most of us, cycling on the open road is 10 x more dangerous than number two. I don’t even know what number two is. I mean, it could be driving, which is exponentially safer than riding a bicycle. ’cause if a bicycle and a car collide, guess who’s gonna win? Even, whichever motorist, whichever pilot was in the wrong, it’s not gonna be much of a contest. So, um, I’m a huge proponent of off-road cycling, bike path cycling if necessary. And if you bristle at this and you don’t think it’s that dangerous ’cause you’re such a good rider, or because you have, so one friend told me that he’s got an app on his phone that has a sensor to warn him of an approaching car from behind.

Brad (24:57):

Oh my gosh, are you freaking kidding me? That is not going to help when some 17-year-old driver is trying to send a text and will, you know, come up right behind and it’s over before your app, uh, starts beeping. I do appreciate the rear view mirrors, and I’ve always used one for decades. And so you can please whatever you do, even if you’re not gonna quit cold Turkey after listening to my show go online and order a rear view mirror that mounts on your helmet, and that way you can see what’s going on behind you without having to turn your head away from what’s in front of you. Because I think a common way to crash is you’re turning your head because you’re worried about an approaching car and you hit a pothole and you go down.

Brad (25:43):

So wear a rear view mirror if you are riding a bicycle prioritize the most safest roads you possibly can, even if that means a little bit of inconvenience, like getting in your car and driving 12 minutes. Because I think a lot of people have that ability to get out into a, a safe area. And I’m not gonna say that rural is necessarily safer than urban. So it’s not as cut and dried as that in many cases. And in many urban environments, they have such an attention to bicycle safety and such a high population of bikers that you get a measure of safety when you’re biking in common areas. PCH where I used to live in Southern California, that stands for Pacific Coast Highway, extremely busy, dangerous highway that runs along the coast for the length of Los Angeles and Malibu and into, uh, Ventura County.

Brad (26:37):

I did a lot of riding on there. And there’s a ton of cyclists on that road all the time. I still contend that it’s super dangerous, but you do get that tiny measure of safety that you might not have if you’re choosing, uh, some rural county highway that has an insufficient shoulder. And you think just because the lack of car population is gonna make you, uh, bulletproof from many potential, uh, danger. That’s not true either. Um, and they have this, uh, shared space concept in Europe where they have, um, uh, bicycles intermingled with, uh, automobiles. And it’s so common that they feel like it’s safer than trying to, uh, separate and do a lot of signage and striping and ways to, attempt to keep the bikes and cars apart because people get lulled into complacency in that case.

Brad (27:30):

And that’s when a car, uh, you know, turns into the bike lane that one time and takes out the biker ’cause they weren’t looking. But in Amsterdam where cycling is ubiquitous, and there’s other examples of this shared space concept working well. The bikers don’t have a bright green lane to pedal in, but they actually fare pretty well because everyone’s aware of them. And that’s what I mean by, uh, cycling in, uh, highly populated cycling routes. I’m also referencing, San Vincente Boulevard in West Los Angeles, which is a thoroughfare that’s busy with fast moving cars, but tons and tons of cyclists and joggers, thereby every motorist on there is a little more aware than perhaps another boulevard that’s not highly populated, but it’s a losing proposition anyway, you slice it. So if you insist on riding your bicycle on the road, realize that it’s 10 x to a hundred x more dangerous than the next most dangerous thing you do in life. Ask yourself about the risk reward payoff, whether it’s absolutely necessary, and go to extreme measures to keep yourself safe out there.

Brad (28:34):

And if I was CEO of the Ironman with that kind of power, and I said, guess what? The 20, 24, 25 and 26 seasons are all gonna be held off road. So better get yourself a mountain bike and start training. And the other cool thing about mountain bikes is that when you use them on pave roads, on, on, on streets and, and, and highways and whatever, you have a more safe position. You have fatter tires so you can navigate obstacles better. I have personally had the experience of taking my mountain bike and nose diving into the bushes off the road because a truck and a trailer was fast approaching on a curve and the trailer was swinging wider than the driver. I’ve also been hit by a boat trailer, in that same dynamic where the driver is driving safely and keeping their car in the lane safely, but they don’t realize the momentum caused by a trailer turning wide.

Brad (29:27):

And so the boat trailer just swung wide. I saw it coming, and it knocked me off of my bike onto the sidewalk. Luckily I wasn’t hurt badly, but that was kind of the last straw for me as an athlete training in Los Angeles, California urban area. I said enough of this already. That was my second bike accident in six months at the hands of a car. And that’s when I moved to Northern California and was out riding in the remote, uh, quiet logging roads and trails in Northern California. Much, much safer place to ride my bike. Okay, how about that? Is that enough on the banning of road cycling theme?

Brad (30:05):

What else am I gonna do as CEO? Oh, you know what, how about drug testing the age groupers? Okay, I am just kidding on that aspect kind of, but, and I don’t follow it very closely, but I know there’s been some whining and controversy about this topic where, um, some of the people picking up the prizes and getting on the podium in the advanced age groups, uh, are being suspected of, or accused, or I think they do do some testing and some people have tested positive for band substances.

Brad (30:34):

Of course, in elite professional Olympic sports, we have to fight this battle really hard, or we’re obligated to do the best we can to try to keep these sports clean. World anti-doping agency has random unannounced out of competition, annual 24 /7 365 possibility. If you’re signed up as a performer in the elite or in the Olympic sports, they can knock on your door anytime and request a sample. And that’s a really, uh, noble move to try to keep sports clean, especially, deter athletes from doping up in the off season and then going to the competition and testing clean because they know how long drugs lead their system. But when we’re talking about amateur sport, I’m not sure it’s a high priority. And if someone wants to dope their asses off and beat you outta that spot on the podium, I think the the planet has worse problems right now.

Brad (31:25):

You know what I mean? I know it’s a bad deal and it probably hurts your feelings to work really hard and try to win that title and end up getting second <laugh> to some 63-year-old who’s got veins bulging all over his body and red skin from, uh, taking extra testosterone. But I’m not, uh, terribly concerned about that at the elite level. Of course, we have to keep refining our approach. The athletes are always gonna be looking for advantages. And this brings to mind, I think this was actually episode one on the Primal Endurance Podcast. Episode one or two were Mark Sisson and I talking in depth about the overall issue of doping in elite sports, especially endurance sports. And for those of you don’t know, Mark served as the anti-doping, anti-doping Commissioner for the sport of triathlon for the International Triathlon Union for many years.

Brad (32:15):

He actually created the first charter for the first drug testing policy and implementation for the sport of triathlon in the, uh, late eighties, early nineties. So he’s been highly involved in this, is, uh, highly aware of all the, uh, the nuances and the moral objections and implications and things that are probably behind the scenes of the average, uh, sports viewer who likes to form this mentality of, oh, there’s a cheater. They’re disgraceful, let’s bust them and kick them out. You’re probably, uh, thinking of Lance Armstrong right now. But if you know even a little bit about the world of cycling and the doping culture that has existed for decades, you realize that during Lance’s era as the greatest cyclist in history really, and one of the greatest endurance athletes of all time, he was competing in a sport that is confirmed to be filthy dirty.

Brad (33:08):

Such that all that giant pack that was racing, the Tour de France that you see on TV when Lance was winning again and again in the yellow Jersey, all those guys were doped off their ass. I shouldn’t say all, but let’s say that, um, the vast majority, uh, 95%, 97% to some clean mid nineties cyclists wanna get on, uh, the podcast and, and, and proclaim that they took what do they call it, Pani. Awa is the, uh, uh, the quip, uh, from the tour tour de France. Writers from decades ago were, uh, I think it was Jacques Quiel, a five time winner once said, you cannot do the tour on Poni awa alone bread and water in French. And so the needles have been going into these guys for decades. It’s part of the culture for for many reasons, including the behavior of the organizers that didn’t wanna really crack down that hard.

Brad (33:58):

And also knowing how extremely difficult these events are. Sisson has advanced a really compelling argument that perhaps we should legalize doping in the elite sports Olympics, and especially endurance sports. Isn’t that crazy? Hear this out. What would, what would happen if we legalized it? It was, it would end the, uh, clandestine doping practices that can oftentimes be unhealthy for the athlete and also also provide an unfair advantage to those who choose to dope while others choose to remain clean. But if we’re all brought into the open and put out on the table, then the elite athletes could get excellent medical care to oversee a properly conducted doping regimen where they were optimizing levels of the important hormones. EPO is the oxygen, the red blood cell boosting hormone. It’s made naturally in the body erythropoietin, and they take the drug called EPO to boost their red blood cell production in the exact same manner that you get when you’re training at high altitude.

Brad (35:02):

And as an offshoot there, if you can afford a $12,000 altitude tent to enclose your bed, uh, in an altitude chamber, you are getting a doping advantage completely legally, ’cause you’re not putting a needle into your body. But it still brings up the moral implications of, Hey, who can afford a $12,000 tent to zip around their their bed every night? And is that fair? And you could argue certainly that it’s not fair. So, if the extreme endurance sports were legalized such as, uh, professional Ironman triathlon racing and marathon running and Tour de France racing, uh, what would you have? Oh, you’d have a bunch of athletes keeling over and dying. ’cause drugs are so dangerous. In fact, the extreme nature of the training and the competition in these sports that I mentioned is so physically unhealthy to the body,

Brad (35:53):

It tanks your hormones so significantly that it’s highly validated to argue that a doped up athlete has less health destructive consequences than someone who’s trying to train and raise for the Ironman or the Tour de France clean without the boosting of hormone replacement. Uh, so if you’re out there training 30 hours a week like a Pro Ironman athlete or a Tour de France athlete, you’re on the red line at all times, like I described about my own career. And you’re constantly tanking your hormones, you’re suppressing your immune system. You’re suppressing the importance sex hormones like testosterone, growth hormone, and you are, uh, often or easily depleting your red blood cell content also. So back in my day as a professional triathlete from 86 to 94, I was age 20 to 30 approximately. I got my blood tested all the time.

Brad (36:50):

Thank you brother Wally, for working in a laboratory where I had easy access. And I would often go in there when I was feeling tired, beat up, burnt out from a lot of travel or a lot of extreme training. And reliably my testosterone would tank down to what is considered hypogonadal. So I would be a candidate for hormone replacement if I were a guy off the street. But of course, I’m competing in elite sport, so I couldn’t take anything to alter my body chemistry. So I would sit there looking at a blood result that said my testosterone was 280 or 290 or 330, and I would also notice a decline in my, uh, hematocrit, which is the important, uh, reader of how much your, uh, red blood cell content in your cells, and that is oxygen carrying. And so people who get iron deficiency anemia have a low hematocrit and they feel like hell, and they’re not delivering enough oxygen to the working muscles and tissues throughout the body.

Brad (37:45):

And so I’d see my hematocrit go from a somewhat healthy 42 or 43. The dopers who use EPO will get it up and over 50. Uh, so I was doing the best I could as a natural athlete and seeing these results like 42 or 43. But when I got tired and burnt out, I would see that hemato dropped to 38 or 37 or 36, and that is significantly low for someone who’s trying to pump a bunch of oxygen through the working muscles in training every day. And what would happen, I would have to go home and sleep and eat a lot of hamburger to get some extra iron in the diet and be patient and allow those testosterone levels and that hematocrit level to rise up naturally. And it would take one, two or three weeks, sometimes six weeks if I was really fried.

Brad (38:32):

And then I would get my hormones and my blood work back up to normal level where I could go out there and train appropriately again and do the same exact freaking thing to myself with, you know, another training block of, uh, efforts that were extremely stressful to the body as revealed by adverse blood values. And so, uh, if I could only imagine having my hormones and my hematocrit pegged for those nine years that I competed on the circuit, oh my gosh, it would be a laughable ridiculous difference. They, they have a confirmed, uh, research showing that EPO provides a 6% advantage in endurance competition. So if I had a 6% advantage, I can go into the other room, get out my file folder and show you my race results from nine years on the triathlon circuit. If I were 6% better in every race that I competed in, I would’ve won easily, virtually every race I competed in and be waiting at the finish after taking a shower and having some scrambled eggs for second place finisher.

Brad (39:32):

’cause 6% over a two hour race, right? 120 minutes, or we usually race like 110 minutes, that would be five minutes or so. <laugh>, you know, five minutes is the difference between first and 15th or 23rd in races on the professional triathlon circuit. So, um, you know, legalizing doping and allowing the athletes to have the optimal body chemistry for events that are so extreme in nature that they’re not realigned with human health. It’s worth taking a breath and thinking about it sometimes. Yeah, maybe that’s not too popular of a take and everyone should be honest and clean and all that, but when they’re not, and when you’re competing in a sport that you believe is not a level playing field, whether it is or not, that’s when everything becomes screwed up. And the morality and the high-mindedness of the individual starts to get muddled in, uh, what you perceive to be unfair circumstances.

Brad (40:34):

I think the best account of this came in Tyler Hamilton’s brilliant book, uh, written with Daniel Coyle called The Secret Race, where he pretty much spilled the beans of what it’s like to be an athlete on the professional cycling scene in Europe. And here’s a young kid, a national cycling champion at University of Colorado Boulder. Nice good. All American guy goes over there, races his heart out. And I think the title of the chapter, was called a thousand Days. ’cause a Thousand Days is about how long you will last on the European cycling scene without doping your ass off to stay up with the pack. And he finally got called into the secret room and they said, boy, we like your heart. We see how hard you pedaled even when you’re falling behind, and you need to get your, uh, vitamin program optimized.

Brad (41:19):

And that was the euphemism they used, uh, to get over into the doping culture and peg that hematocrit. And going from getting dropped off the back of the pat to 6% better, uh, means that you’re going to win Olympic gold medals like Tyler Hamilton did. Sadly, he tested positive and the gold medal was stripped. But who’s holding that gold medal now? Sometimes it’s no one. Like when Lance was stripped of his seven Tour de France titles from 1999 to 2005, guess who the title was awarded to Nobody because the, the doping culture was so exposed with the, uh, raids of the doctor’s office, operation Puerto it was called, uh, all this stuff came out in the wash, such that they decided to vacate the Tour de France title for those seven years. Kind of ridiculous ’cause like, look, Lance was the fastest guy to the finish line.

Brad (42:09):

If everyone was doping, why not give him <laugh>, allow him to keep his yellow jerseys? I think he said F you to whoever asked for the yellow jerseys back. I like when people do that. Like Reggie Bush, the Heisman Trophy winner at USC. He had to return his Heisman Trophy because his family took money from a sports agent. Isn’t that ridiculous? Now, in this day and age, when you see all the college athletes getting those big dollars on those NIL deals, which I think is an awesome thing. Yeah, I should probably finish up on this discussion of doping because I know there’s a lot of controversy also about the transgender athletes competing as females. And clearly there’s a huge advantage to having a different hormonal profile for however many years prior to transitioning and entering in the female division.

Brad (42:57):

And it’s also true that the hormonal advantage experienced in prior years lingers for quite some time. This is the same idea as a bodybuilder or a athlete in another sport like football, uh, doping their asses off in the off season and then go and testing cleanly, but still having this amazing block of training where they were hormonally boosted and getting the fitness benefits that accrue and the muscle mass in the case of the bodybuilder. So even though they test clean, obviously that drug passed, or in the case that I’m referencing, uh, that passed as a male with male hormonal profile is a huge unfair advantage. Now in Olympics, professional competition, this is a huge dilemma. There’s all kinds of moral implications and, uh, how to legislate and identify. There’s been cases of, uh, elite athletes like Olympic gold medal, uh, 800 meter runner Castor Semenya from South Africa, who, who was competing in the female division, but has unusual blood findings and ambiguity, they call it.

Brad (44:04):

And I’m not an expert, so I don’t want to get into that. But again, just like I talked about with, um, drug testing, amateur athletes, if some transgender athlete wants to compete as a female and they’re gonna beat everybody because they’re stronger and have, uh, uh, all those advantages, I think we have bigger problems in the world. I know it’s not fair, but I also know that these people have been marginalized in so many ways and had such a brutally tough journey to get to that point where they have the courage to honor the emotions and, and the thoughts and the inclinations and, and, and, you know, transition to what they feel is a more appropriate existence. Oh my gosh, I think the outrage and the singling out, um, is probably a little bit overboard when we’re talking about competing for fun anyway.

Brad (44:54):

I mean, look, the essence of sport is to pursue a personal growth opportunity, personal challenge. And I think that goes for everybody. And this is regardless of whether you make the podium or maybe you got bumped off and you were fourth place to some transgender athletes ahead of you, and you’re really bitter about that, but maybe you should just be proud of the amazing performance that you did to get to fourth place. So that’s my little sassy comeback on another potentially controversial topic. But I do give a lot of credit to those people who are on that, on that rough and courageous road, to be the best that they can be. And maybe we can, uh, tone things down and, and cut, uh, people a break. And, I really love the post by the triathlon legend, Jan Feno, uh, reacting to the news, uh, that one of his peers on the triathlon circuit tested positive for EPO and admitted to it, uh, <laugh>.

Brad (45:50):

Um, and with a, a, a confession that, uh, for some reason, uh, rubbed me the wrong way. It’s like, if you’re caught and you’re busted and you’re guilty and step up there, confess, say you’re sorry. But I think, um, what I saw was a really, uh, a backdoor confession, and it shows that person has a lot of personal growth ahead of them, <laugh> and, and more challenges, right? I mean, own up to it. Come on. Same with Marian Jones and her famous press conference in the early two thousands where the takeaway pull quote that I remember was what I thought was muscle cream for my aching muscles turned out to be performance enhancing drugs. Oh, you thought that was just some lotion for your hamstringing, like the, uh, the icy hot tiger bomb? Yeah, right. Come on, just spill all the beans because then we can, uh, at least your, uh, your disgraceful act can work toward moving sports forward and pursuing a level playing field.

Brad (46:53):

So what Jan Feno said was, you know, the reason he got into the sport of triathlon, was to, uh, a challenge himself at a young age. He put a picture up of him and his father cycling up a hill when was just a kid. And he says it’s given him so many rewards, but the rewards have been, personally gratifying. Therefore, the decision to dope is so strange because really, like, what do you wanna do win the race knowing that you have gained an unfair advantage over competitors. So as I give Lance Armstrong and all the other guys, Tyler Hamilton, a huge break for making virtually the only possible decision they could make to compete at the highest level of professional cycling. I have some harsh words and feelings for those who are cheating in sports that are by and large believed to be clean and boy, to get an unfair advantage and cheat out your peers and people that you train with and socialize with.

Brad (47:46):

That shows some real problems with character there. And there’s absolutely no excuse. Um, luckily my time on the professional circuit, 86 to 94 predated the advent of EPO, which was really the game changing drug in endurance sports. So pretty much didn’t exist except for some cyclists in, in the Netherlands who were testing it out. And a lot of them died in their sleep. I believe it was like 24 high-level Dutch cyclists died, um, in the late eighties, early nineties from screwing around with EPO when they didn’t really know how to use it. Uh, but back to my career, um, there was minimal suspicion of performance enhancing drug use, but in fact, there were some isolated occasions of athletes testing positive that I competed against frequently and took a lot of money outta my pocket because there were some prominent elite athletes.

Brad (48:36):

And I have only, you know, really, um, uh, uh, criticism and, uh, disgraceful feelings for those people that cheated, what they pretty much knew were a bunch of clean athletes. So there we go. Um, it’s all circumstantial and it’s helpful to, uh, understand and appreciate the big picture. Thank you for having me as your CEO for one day. And I think now I’m gonna resign and let someone else step up and hopefully they’ll honor some of my suggestions. Hey, you want to comment? Oh my gosh, I’d love to hear from you, whatever you got. Even if you’re in disagreement, uh, and strong disagreement, it’ll be fun fodder. Maybe I’ll read it on the Q and A show. So please email podcast@bradventures.com. I appreciate all feedback, commentary, and opinion sharing as we work on this healthy fit lifestyle together. Thanks a lot for listening or watching.

Brad (49:33):

I hope you enjoy this episode and encourage you to check out the Primal Endurance Mastery course@primalendurance.fit. This is the ultimate online educational experience where you can learn from the world’s great coaches and trainers, diet, peak performance and recovery experts, as well as lengthy one-on-one interviews from several of the greatest endurance athletes of all time, not published anywhere else. It’s a major educational experience with hundreds of videos, but you can get free access to a mini course with an ebook summary of the Primal Endurance Approach and nine Step-by-step videos on how to become a primal endurance athlete. This mini course will help you develop a strong, basic understanding of this all-encompassing approach to endurance training that includes primal aligned eating to escape carbohydrate dependency, and enhance fat metabolism. Building an aerobic base with comfortably paced workouts, strategically introducing high intensity strength and sprint workouts, emphasizing rest, recovery, and annual periodization. And finally, cultivating an intuitive approach to training. Instead of the usual robotic approach of fixed weekly workout schedules, just head over to Primal Endurance Fit and learn all about the course and how we can help you go faster and preserve your health while you’re at it.