Q&A: Can I Raise My MAF Heart Rate (NO!), The Stress Of Keto Endurance Training, Breathing For CO2 Tolerance

It’s been YEARS since we did a Q&A show on Primal Endurance (including the podcast being on pause from 2019 to 2022).

We have some excellent and widely relevant questions, including: Can I raise my MAF training heart rate if I feel comfortable? A listener asks about ketogenic endurance training—yes, it can prompt quick benefits in metabolic flexibility and escaping carb dependency, but can it become too stressful over time? Other questions include: how to proceed comfortably with minimalist footwear, is striving for maximum cellular energy status to support performance and recovery the most sensible and effective longevity strategy for healthy, active, fit enthusiasts?, and if practicing nasal diaphragmatic minimized breathing can confer a performance advantage with increased O2 delivery and less workout stress.

Enjoy, and please contribute to the conversation by emailing podcast@bradventures.com!

TIMESTAMPS:

Heather is rather new to the sport of triathlon. She finds it difficult to stick with the slower heart rate in her training. Is that okay? Brad explains why the MAF rate is so important. [00:24]

Brad would strongly urge everyone listening to reject the obsession with pace per mile and just train according to your heart rate and according to the desired duration of your workouts. [08:02]

You should look at it as three types of workouts: key workouts, break even workouts, and recovery workouts. [10:10]

Heather also asks: Should I opt for fast walking until improvement in my aerobic fitness allow for a jogging pace? The heart rate is the focus. [14:07]

Same Heather, different area of concern, asking about diet. Keto diet is stressful. The main benefit is getting rid of processed carbohydrates that are difficult to digest and interfere with your body’s ability to burn energy internally. [18:54]

The elevation of resting heart rate from combining keto and endurance training is a red flag. [25:45]

Stacy Clark is a very active athlete at age 59, asking about her training regimen and whether she should do some faster runs or sprinting maybe once a week. [28:29]

Ryan Baxter talks about getting away from devotion to fasting or low carb and keto and going to good sensible intake of nutritious foods that fuel his performance and recovery goals. He added an additional 700 calories per day and gained no weight. [35:17]

The single most powerful intervention to promote longevity is exercise. If you fast for 48 hours, you get wonderful benefits but you can get the same benefit from doing an intense one-hour workout. [40:48]

Breathing is playing an important role. If the muscle is not getting enough oxygen, the muscle will burn glucose rather than fat. [47:07]

LINKS:

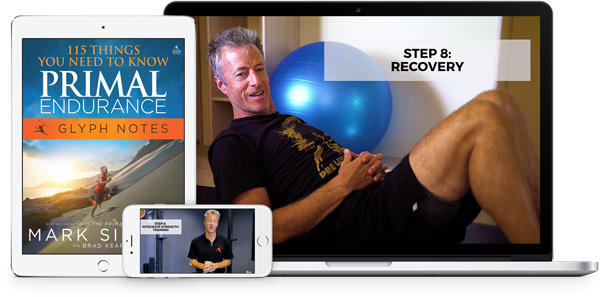

- Primal Endurance Mastery course (FREE bag of Whey Protein Superfuel if you sign up for the full course, just email us!)

- Brad Kearns.com

- Brad’s Shopping page

- PrimalEndrance.fit

- Brad’s Running Technique

- Running Drills for Beginners

- Carnivore Score Food Ranking Chart

- Peluva.com

- Outlive

- Why I Stopped Fasting (Mutzel)

- Oxygen Advantage

- shiftadapt.com

- Podcast on breathing

TRANSCRIPT:

Brad (00:01):

Welcome to the Return of the Primal Endurance Podcast. This is your host, Brad Kearns, and we are going on a journey to a kinder, gentler, smarter, more fun, more effective way to train for ambitious endurance goals. Visit Primal endurance.fit to join the community and enroll in our free video course.

Brad (00:24):

Hello, listeners. It is time. It’s been a long time coming for another episode of Q and A on the Primal Endurance Podcast. You know, we had that long break, uh, going back to 2019 when the show went dark for a while. We’re coming back with a vengeance. We’ve had some great guests and some great series of informational podcasts, and now it’s time to dig into quite a long list of very interesting and I think helpful questions for everyone out there fighting that battle, trying to get better, trying to do it the right way, preserve health and enjoy the process along the way. So we’re gonna start with Heather. Um, she says, I’m a relatively new endurance athlete. My first event was 2018, which was a full Ironman triathlon. Hey, welcome to triathlon. Guess what? There’s shorter events out there, but hey, nice, nice way to get on the board.

Brad (01:18):

That reminds me of my friend Martin Brauns, former podcast guest on the B.rad podcast. His first triathlon that he ever participated in was the Ultraman in Hawaii . Can you believe ttat? He was out there serving as a crew member for his friend Vito Bialla, multi-time finisher, the Ultraman. And he was so inspired by it. He says, you know what, I’m gonna do this. And he went back the next year, or maybe another year later and did the extreme grueling Ultraman. It’s a three day triathlon held on the big island of Hawaii, and the first day is a six mile swim and a 90 mile bike. The second day is 170 mile bike ride, and the third day is a double marathon. 52 mile run. Yeah, his first triathlon ever. So Heather doing her first triathlon Iron Man in 2018. Since then, I’ve completed 50 k, a virtual solo 40 mile run, a solo a hundred K run.

Brad (02:18):

Wow, I didn’t know, uh, they had so many of those virtual runs. That’s pretty crazy . That’s a good effort to go out there and do it by yourself and then have that online connection. Must be kind of fun when you finish to go and upload your data. I’m really fascinated by the low heart rate approach, says, Heather, I have not been getting any faster running at my usual heart rate zones, my usual training. So I want to be able to do something that’ll help me reach my athletic potential. I’ve been exploring low heart rate training, but have not been able to consistently stick with it for several reasons. Hey, thanks for pouring your heart out here, Heather, because, it is a tough thing to stick with, uh, because you’re forced to go a lot slower than you, uh, feel like is comfortable and that you’re comfortably capable of.

Brad (03:03):

But the payoff comes down the line as you are training your aerobic system rather than a mix of aerobic and anaerobic. So here’s why Heather is not able to stick with it. First, my heart rate seems disconnected from my perceived exertion. That is, I feel fine cardiovascularly, I’m nasal breathing, I’m at a conversational pace, but my heart rate might be five to 10 beats above what is my maximum aerobic calculation of 180 minus age question. Do some people’s hearts just run faster? No pun intended. If this is the case, can I train by perceived exertion of what feels easy as opposed to this strict heart rate? Ah, guess what I mean? Phil Maffetone, his life’s work emphasizes this point so strongly that we have to go by the calculation. We cannot inch up there and get permission for one reason or another to bump up our MAF heart rate by five or 10 beats except for his very alienated, uh, question and answer where you’re allowed to add five or subtract five or subtract 10 if you have certain circumstances.

Brad (04:12):

And the subtractions are for people that have been frequently sick, injured or novices. If you’re on prescription medication, he wants you to subtract 10 from your 180 minus age rate. And then the add the all precious add five are for those who have been, uh, excelling without injury or interruption. Great competitive results. There is some, hall pass for the older athletes, like people in my age group where pretty soon your cardiovascular function is not declining at the same rate as your annual years. And so even at age 58 where my maximum aerobic heart rate would be 122, I typically run, uh, five beats faster than that comfortably. So now, um, this perceived exertion is such a fluid notion and it’s influenced by so many things that it’s much, much better to honor this MAF heart rate training protocol of 180 minus age and keep your heart rate at that comfortable zone even though it feels extremely comfortable.

Brad (05:12):

And even though you feel just fine if it creeps up by five or 10 beats. And I say this from years of experience, that if you go out there and you run a little bit over your maximum aerobic heart rate on a regular basis for years and years, months and months, whatever, you’re not going to improve as reliably or as consistently as if you really take care of your aerobic system in training. Now, what is the maximum aerobic function heart rate, that 180 minus age calculation representing of in, in laboratory speak? Guess what? That is the point of maximum fat oxidation per minute. So you are burning the highest rate of fat at your maximum aerobic heart rate. And if you were to speed up, if you were to increase your heart rate, of course you would be burning more calories per minute all the way up to running tempo or running sprint theoretically.

Brad (06:07):

But as soon as you leave that maximum aerobic number, you start to bring in glucose burning into the equation. And that’s not what we want as our foundation for endurance athletes. So you wanna burn the most fat possible per minute. That’s what happens at your maximum aerobic heart rate. Second, this is back to Heather’s, uh, reasons I’m training for a hundred mile runs, this usually requires lots of training miles. Since I’m a slower athlete, I’m running 12 or 13 minute miles. And so if I have to slow down further to accommodate low heart rate training, this might mean I’m going to 14 minute mile. There’s not enough hours in the day for me to fulfill life obligations, run this slowly and get in the miles prescribed on my training plan. How does a slower athlete strike a balance between running the miles necessary and running at the pace, uh, necessary for aerobic improvement?

Brad (07:03):

Well, here’s the thing. Your brain and your body do not have any notion of miles. They only have the, uh, the association with time spent exercising get the difference? So if you’re training for a long distance race, um, you’re gonna be doing two hour runs, three hour runs, one hour runs, 30 minute runs, and so it’s much better and more sensible to, uh, track your training by duration rather than the number of miles. Similarly, if I dropped you off at the top of a paved road at a slight gentle grade of 4% and had you run 10 miles downhill on that nice straight paved road , that would be a lot easier than doing a 10 mile trail ascent where you’re gaining 1700 feet on the 10 mile course. So it’s completely irrelevant how many miles you’re running and it’s vastly more relevant how many hours you are running and at what heart rate.

Brad (08:02):

So if you’re at altitude, if it’s hot weather, if it’s a difficult trail, all these things will be reflected in the heart rate that you’re running at. So I would strongly urge everyone listening to reject the obsession with pace per mile and just train according to your heart rate and according to the desired duration of your workouts. Now, when you get into a race, of course you’re training for the Boston Marathon for eight months and you’re running on trails and you’re running in different cities when you’re traveling, it’s hot, it’s cold, it’s whatever. And on race day, of course, you’re gonna set a goal and try to keep a certain pace and a and and finish in a certain time, but that’s what races are for. The rest of it is training. Okay, I think I made my point there where we want to get you out of this, uh, thinking that is so common.

Brad (08:50):

And as she writes in her question, my prescribed training, training plan. So someone or something is telling her that to prepare for a hundred mile run, you need to get in some 35 mile training runs nonsense. You need to get in some long hours in training. But again, if I dropped you off at the top of the paved road at a 4% grade and had you run 35 miles downhill, that’s a lot different than doing the trail run. So if you can get in the quote unquote five hour training session and two four hour training sessions and four, three hour training sessions or whatever protocol you’re following, hopefully from an expert and not just from a magazine or an internet resource, but really I like to simplify this and I spend a lot of time and energy, uh, in the online course and in the book saying, look, um, what you wanna focus on is key workouts, or as Mark Sisson has called them for many years, breakthrough workouts.

Brad (09:43):

So you have this baseline level of training and conditioning and practicing in your chosen events in your chosen sports. And then once in a while, you want to challenge the body to a peak performance effort that stimulates a fitness improvement. So this would be running for longer duration than you have before, or this would be going, uh, in a tempo or a track workout where you’re trying to hit a certain time that might be better than your last one.

Brad (10:10):

These key workouts or breakthrough workouts, a prompt a fitness improvement because they challenge the body to perform beyond the typical level of the day in day in, day in, day out training patterns. So if you wanna en envision every workout in one of three boxes, it’s the key workouts, the big challenging ones, it’s the maintenance workouts or break even workouts as Mark Sisson has called them. Or it’s a recovery workout, which is a workout that’s specifically designed to be extremely minimally stressful and it will help you bounce back from the workouts where you really challenge your body and your musculoskeletal system and so forth. Okay? So, um, a slower athlete strikes that balance by counting hours instead of miles. And on the first part of the question, as I emphasized a lot, uh, can I add some more beats? No, you cannot . And third, here we go. It seems at the slower pace, results in greater force applied when I run, uh, and I have more joint discomfort than I normally have. Uh, assuming running at higher speeds, uh, I still feel compelled to try and run even though it’s painfully slow. I think it changes my form. Should someone like me opt for fast walking until improvements in my aerobic fitness allow for a jogging pace that does not compromise form.

Brad (11:28):

Thank you so much. I love the Primal Endurance podcast, da da da da. Uh, that’s an interesting point Heather makes at the end. And I’ve heard this, uh, I’ve received, uh, many comments on my YouTube video, uh, the Brad Kearn’s running technique instruction. It’s the viral video. It’s got 2.2 million views, thank you very much. YouTube, world algorithm, whatever, how so many people saw it. I don’t know, I’d love to have more of those going up there to the 2 million views. Uh, but I talk about running technique and I make the point in the video that these technique attributes apply at all running speeds from sprinting all the way down to jogging. You still want to maximize the, uh, flexibility and the, uh, the, uh, force production potential of the ankle joint, uh, when you’re running even at a slow speed. So you’re not shuffling your feet along with what I call lazy foot.

Brad (12:19):

You’re doors flexing that foot as soon as it leaves the ground and you’re getting that achilles tendon into the mix to provide some forward propulsion even if you’re jogging 10 minute mile or 13 minute mile. And occasionally I hear from people saying that it hurts more to run with this, uh, supposedly correct technique, uh, and they like shuffling better. And so, um, when you’re running slower and you contend that it’s more difficult for the musculoskeletal system, this can be, uh, pretty easily countered. If you were to run on a force plate, that’s a laboratory that determines, uh, how much impact force is happening with each stride. You would notice that the slower you go the less impact with each stride, obviously. So the slower you go, you’re gonna have less impact on the muscles, joints, connective tissue, that’s just, uh, physics right there. And so if it feels funny, it’s probably cuz you’re just not used to it.

Brad (13:15):

And I also contend that if you use the foot and the achilles tendon properly by dorsa flexing the foot throughout the stride pattern and making that circular, that bicycle motion that I describe on the video, that is the most efficient way for the human to run with the least impact trauma, even less so than the shuffling stride that you see with a lot of long distance runners. So I’m gonna reject all the, uh, counter-arguments saying that it feels better to shuffle along. That’s an inefficient use of the, uh, all the muscles and joints and achilles tendon. And guess what? Your hip flexors are still gonna go at mile 20 when you shuffle the first 20 miles rather than run correctly. So there’s no way around it except to exhibit the most precise and optimal technique that you can at all running speeds.

Brad (14:07):

Now Heather brings in that other wrinkle where it says, should I opt for fast walking until improvements in my aerobic fitness allow for a jogging pace? And that’s not a bad idea because again, we’re going by heart rate. So if you are heading up toward your maximum aerobic heart rate with a fast walk, that is an outstanding training session. There is no need to jog unless you get fit enough to jog comfortably. And I’ve shut down some of the contention here, but I also wanna acknowledge that I know how it feels funny to jog really, really slowly in the name of keeping your heart rate steady. So maybe you would prefer a fast walk and build your fitness that way. It will not be long until you can break into a comfortable jog instead of what feels like a lame jog because your heart watch is beeping. And I’ve talked about this so much over the years of shows on this podcast, but I just want to emphasize one more time, when you feel frustrated about limiting your effort to your maximum aerobic heart rate, please reference the example of the great elite athletes of the world, like a marathon runner.

Brad (15:16):

Eluid Kipchoge may be the greatest endurance athlete of all time up there with Lance Armstrong and some of the other luminaries, but the greatest marathoner of all time for sure. On his easy day, he runs, I believe it’s 18 miles at a six minute pace at high altitude , which by most, uh, all mere mortal standards and even uh, many elite athletes, that’s not an easy day, that’s a very impressive workout. But we have to unwind this a little bit and realize that his easy pace of six minute mile is a minute and a half slower than his marathon race pace when he runs 1:59, running around four minutes, 32 seconds a mile. So he is running comfortably well below his maximum aerobic heart rate at a six minute mile. Holy crap, go try to run a six minute mile. Feels like a sprint to me and I’m in pretty good shape.

Brad (16:11):

But that is actually moving quite impressively. But the reference and the analogy that we have to draw here is that a six minute mile to him, a minute and a half slower than his marathon race pace, what’s a minute and a half slower than your marathon race pace? Is it an 11:30? Is it a 14:30? Is it a 16 minute mile? Is it a 10 minute mile if you’re a badass and you can run a marathon at eight 30 pace? That’s the reference point we have to think about and the stress impact on the body of our easy workouts and our aerobic heart rate training runs. So if you’re frustrated at a brisk walk, that is exactly the same training stimulus as a six-minute mile at high altitude for Kipchoge. So we don’t want you to cross over into this training pattern where you are routinely exceeding your maximum aerobic heart rate because it’s so easy to run at that pace.

Brad (17:07):

You’re training harder than fricking Kipchoge because he rarely exceeds that 80% level of effort. And you can read great articles about his training log, which he has posted for all to examine on the internet and the exercise physiologists have gone to town and tried to calculate out everything and compare everything. So you can realize that 80% exertion is what the great elite runners of the world are doing. There’s certainly no justification for you to push yourself relatively harder than an elite athlete. And there is tons of justification for you to back off a bit or a lot from the model presented by the elite athletes because you probably have job, family, personal responsibilities, a more hectic and more stressful lifestyle than an elite athlete who is training and eating and sleeping. Okay, I hope I’ve emphasized the point enough here, how important it is to take care of your body and limit your efforts to the aerobic zone when that is the intended effect of the workout.

Brad (18:10):

So, I exchanged email with Heather, and as I spoke the answer here she got the answer by email and she says, oh my gosh, thank you. This information is so reassuring. I’ve been stuck in the kill yourself to improve approach for so long. It’s hard to go outside of that comfort zone, especially as a type A like so many of us are. Trust the process and be patient. We’ll need to be the new model. I knew scientifically that it didn’t make much sense that running more slowly could be causing problems. I just got back from a run and felt much smoother this time around. I’m looking forward to checking out your instruction video and refining some technique. We’ll have that link in the show notes or just remember to go to YouTube and type in Brad Kearn’s Running Technique Instruction. I think you’re gonna love this video. Very helpful. I had no idea such a resource existed

Brad (18:54):

Okay, now we go to another entire can of worms opening and it happens that it still came from the prolific Heather, but now she’s going into diet. Look at all this free coaching she got from writing into the show. I love it, man. I’m Heather, who previously wrote about low heart rate training for longer events. Now I’ve gone all in on this whole scene about keto endurance training and I’m in the ketogenic diet. I like the lifestyle I eat when I’m hungry, which is far less often, and I don’t eat when I’m not hungry. My debilitating sugar cravings are drastically reduced. It’s very freeing. Now, before we go into her complaint or her concern about her transition to keto, I wanna set the stage properly and realize that if you’re in that carbohydrate dependency model where she admittedly was training at a slightly higher heart rate than maximum aerobic, so she was stimulating glucose burning and that was very likely leaking into her dietary habits.

Brad (20:00):

As most endurance athletes know, you go out there, you burn a lot of calories, , some of them sugar, you come home and you got that free pass to enjoy and indulge and have carbohydrate cravings, sugar cravings. So now reducing those sugar craving beings suggests that she’s achieved a certain level of metabolic flexibility and fat adaptation so she doesn’t continually have to live on doses of sugar. So indeed that is very freeing, as she says. But I want to highlight that this transition over into keto is a departure from carbohydrate dependency. Then we have to sit back a little bit and look at long-term big picture best options and best interest for the individual and see if this is something that’s sustainable or is it just a transition point where she can optimize carbohydrate intake without worrying about staying at that very low ketogenic level, especially as an endurance athlete.

Brad (21:01):

But just go according to the optimal level of nutritious carbs in the diet and avoid some of the fallout and problems that come from an overly stressful approach to life. And keto endurance training in general, because keto by definition is stressful and so is endurance training. And so here’s Heather’s complaint. As I’ve teed up properly, my resting heart rate has raised almost 15 beats since I reduced carbohydrate intake in my diet. It’s high all day when I’m eating, uh, 30 to 35 net carbs a day. Now, is this a side effect of ketosis? Is it common? Is it something that goes away when I become fat adapted? I always thought that my low resting heart rate seemed like a badge of honor as an athlete. And as silly as it sounds, I measure my fitness by it. No, that’s not silly at all.

Brad (21:53):

And a resting heart rate indicates a strong cardiovascular system and seeing a trending of lower on the resting heart rate means that you’re getting in better shape, generally speaking, if your heart rate’s elevated 15 beats, this could imply that you are overstimulating the fight or flight response, which is associated with elevated heart rate. And so you’re in a chronically stressful state because you are endurance training and trying to adhere to that extremely low carbohydrate intake where she says 30 to 35 net carbs a day. So this is an undesirable response to ketogenic diet. And my immediate advice would be try to experiment with optimal carbohydrate intake by bringing back in nutritious, easy to digest carbohydrates. And as you may have learned from the carnivore scores, food rankings chart that you can download for free at bradkearns.com, there are carbohydrates that are offering minimal nutrition and more difficult to digest.

Brad (23:01):

And there are those that are nutritious and easy to digest. And the centerpiece there is fruit. Um, one of the great foods of human evolution for millions of years. And somehow it’s become marginalized in modern times as people make this blanket effort to lower their carbohydrate intake and feel better. That’s the promise of keto and other low-carb diets. Many of those which I’ve, uh, touted, uh, enthusiastically and written books about. So I don’t wanna be here saying that I’ve completely turned the corner and don’t see any value or benefit from low carb or keto. But I think the main benefit is getting rid of processed carbohydrates that are difficult to digest and interfere with your body’s ability to burn energy internally. And that would be everything in the grains and legumes family, which so many people are highly sensitive to.

Brad (23:53):

And also, as we know from the emergence of the carnivore diet movement, that includes the often, commonly, uh, allotted categories of roots, seeds, stems and leaves. So things like nuts and seeds, which have so many nutritional value, so much nutritional value. My Macadamia Nutbutter can potentially be problematic if someone has trouble, uh, digesting, uh, those particular foods, which many people do have nut allergies as we know. Um, and the, the root seeds, stents and leaves are the stems and leaves are the four categories. So you’re also talking about things like your kale smoothie and your salad and your stir fry. And many of the lauded superfood of the plant kingdom can be potentially problematic, especially when they’re consumed in raw form, which is the most difficult to digest. So it’s something worth examining for people when they are slamming those kale smoothies in the name of health.

Brad (24:50):

Now, if someone like Heather were to experiment with increasing carbohydrate intake, I’d rather see it coming from the easy to digest tubers like sweet potatoes and those in that category. White rice is often touted as one of the easier to digest carbohydrates with extremely minimal, uh, anti nutrient concerns. Unlike the foods in the categories of root seeds stems and leaves, the kale smoothies, the salads, uh, nuts and seeds, things like that. So you can try for some sweet potatoes, lots of fruit intake, perhaps even dried fruit. J Feldman, my frequent guest on the B.rad podcast, the Energy Balance podcast host, he says, orange juice is okay, especially for athletes. So it’s an awakening to think that you can strive for optimal by adding back, uh, an appropriate level of nutritious carbohydrates, especially if you’re out there burning calories in hard training.

Brad (25:45):

And the elevation of resting heart rate from combining keto and endurance training is a red flag that you are stressing the body too much. So again, look at your overall stress scoreboard in life, even get out a piece of paper and write on one side, um, stressors. And on the other side you can, uh, write, rest, rejuvenation, recovery, sleep. And of course you have your evening block of sleep. You have your times when you are disciplined enough to put away your technology and engage with nature, uh, watching the birds , writing down in your bird watching journal, what kind of bird you just saw, things that are relaxing and nourishing, taking a bath in the evening, all that kind of fun stuff goes on one side of the balance scale. And then you’re gonna see a lot of things on the other side of the balance scale.

Brad (26:30):

And you have to write ketogenic diet in there. You have to write endurance training in there. In contrast, if you were to try and optimize carbon intake and if refuel yourself optimally, uh, as soon as you’re finished exercising, then the diet becomes a way to rest, repair, recover, and rejuvenate. You see the difference here? So deliberately restricting carbohydrates to get the, uh, the promised health benefits of ketogenic diet. These health benefits come from the stress mechanisms that are kicked into gear when you go keto. One of the main ones, of course, is reducing excess body fat. So if you’ve been in an existence of overfeeding and under exercising especially, or carrying excess body fat due to overfeeding, even if you exercise a lot and you start to restrict your caloric intake by any means necessary by any strategy you desire, you are going to get that health benefit of improving your metabolic markers and dropping excess body fats.

Brad (27:31):

And that’s an all-around huge win. But then it comes time to look at long-term optimization. You wanna get the extra fat off your body that’s mostly and best achieved by eliminating processed foods. And then we can decide, hey, as an athlete, I have competitive goals. I wanna recover and I wanna optimize intake of nutritious carbohydrates. And very good suggestion to continue to, uh, discard the processed carbohydrates that are difficult to digest. So that’s a lot of the sugars and, uh, exotic Starbucks cocktails and the, um, you know, reaching for the treats because you did so much training. There’s no call for that, especially in a hard training, high performing endurance athlete because we have greater needs for performance and recovery and nutritional density than someone who’s not asking a lot from their body. All right, well that was a good half hour just on Heather. Awesome, Heather, thanks a lot.

Brad (28:29):

Now we go to Stacy Clark. I’ve been reading your Primal Endurance book. I’m 59 years old and I love your advice for the more seasoned athletes out there. I’ve run a few races over the last 20 years, uh, not in a while. The last one was the 10 mile or the half marathon in Virginia Beach six years ago now I got another one coming up. I currently run a few times a week in my Vibrams and watch my heart rate staying around 1 20, 1 21. So that’s appropriate for someone who’s almost 60. I’m also doing some micro workouts throughout the day, like pushups every time I go upstairs so I can get an angled pushup, you know, on the, on the first steps. I also do 20 squats three to four times a day. What an awesome regimen. Congratulations, Stacy. I’m also pretty much eating two meals a day and low carb.

Brad (29:17):

I also do strength training with weights and I exercise, uh, with a bar and a band once a week here. Ah, my questions, should I do any, uh, targeting or progression runs or high intensity repeat training once a week? If my max heart rate for endurance exercise is 180 minus age, what should my heart rate look like during a high intensity workout? Like a HIIRT session, high intensity repeat training? I’m not an elite athlete. I find that signing up for a race helps motivate me and take care of myself. And also being low carb running in my Vibrams, my knees no longer hurt. So this is someone who has adapted over time to running in minimalist shoes and getting the most out of their feet, getting great strengthening effect on their feet, but doing it the right way and not inviting that injury risk that Vibram got in so much trouble for and got class action lawsuit because someone said, I wore these and I got injured.

Brad (30:10):

It was kind of ridiculous, but it did illustrate a good point that the minimalist footwear is, uh, so beneficial in so many ways, but you want to ease into it, especially when it comes to using them during exercise. But the best way to ease into it is to go to peluva.com right now, P E L U A, and check out Mark Sisson’s, awesome new company that he recently founded with his son Kyle. And they’re kicking some ass putting out these really fashionable, stylish, minimalist shoes with the articulated, uh, five different slots for the toes, just like the Vibram. But these have a little bit of extra padding. They’re a little more designed for, multipurpose, functional, safe use. And I absolutely love my pair. I’ve been running in them, sprinting in them going out to fashionable, uh, establishments in Las Vegas. They’re really cool.

Brad (31:00):

I think you’re gonna like ’em. And, um, that’s a nice little plug there for what Mark’s been up to in his longtime fascination with minimalist footwear. So good luck with your, uh, your efforts there, Stacy. And now let’s get to the questions. Should I do any faster runs, uh, or, or, or just once a week, do a sprint workout and this is all, you know, based on the relative importance of the distinct goals that you have set. So most listening here have some form of goal, probably an endurance event based on the name of the podcast. And if you’re training for an extreme endurance event, like a half marathon coming up, like Stacy writes, of course, you’re most bang for your buck, the most return on investment is going to come from over distance, aerobic workouts, and then some icing on the cake.

Brad (31:49):

Once in a while could be a high intensity repeat session, like a sprint workout, but you just definitely wanna increase your competency at the aerobic heart rates and perform and recover from those challenging workouts where you’re going over distance. You’re trying to extend the time of your workout and put most of your energy into that. Because if you think about it, you’re gonna do some baseline exercises of whatever you’re running for 30 to 45 minutes, then you’re gonna challenge yourself by going long once in a while, and then you’re gonna be recovering from those longer distance runs and then gearing up for another long distance run coming up in the future. And so trying to sprinkle in a lot of high intensity effort there when your stated goals a half marathon is not necessary. But we also get people who have an assortment of goals and wanna to have overall broad-based fitness competency.

Brad (32:41):

It’s so cool now that the hybrid athlete is coming into vogue and these sensations on YouTube who are doing these combination efforts like deadlifting 500 pounds and then going and running a five minute mile immediately after. So amazing. Fergus Crawley, I met this guy over at the Mark Bell podcast. He had flown in from England and, uh, he’s had some amazing like double Ironman performance and deadlifting 600 pounds or some crazy stuff. You know, in the morning you’ll go in the gym, do his warmup, deadlift an incredible weight and then go run 50 kilometers, you know. So, um, the hybrid athlete is what it’s called where they’re showing competency in extreme, uh, strength and power as well as endurance Mark Bell. How can you get a better example than that? Uh, a record setting professional power lifter when he weighed in at 330 pounds and was squatting a thousand pounds or something.

Brad (33:34):

And now he’s about to, uh, participate in his first Boston Marathon. An amazing transition from giant power lifter to competent endurance runner. Yeah, so do whatever you want is the answer, Stacy. But for someone with generalized fitness goals, they’re not going for the podium in their endurance event. Hey, just get out there and, try to become competent in sprinting as well as the old primal blueprint fitness pyramid indicated. Um, our, our genes are best served by the ancestral style behaviors that give us broad base fitness competency, and that is a mix of frequent general everyday movement, including aerobic activity, including formal, uh, cardiovascular sessions in the aerobic heart rate, and then, uh, regular lifting of heavy things, strength training, resistance training, and then sprinting occasionally once a week is plenty, but you do wanna get competent at sprinting. I think it’s one of the quintessential human activities and has so many health benefits, longevity benefits, peak performance benefits, even.

Brad (34:43):

cognitive benefits have been shown associated with sprinting. And it also gets you better, more competent at all lower levels of exercise intensity. So if you can put out some real power and exhibit some good technique while sprinting, you are going to become a better endurance runner because you’re activating all the same energy systems and teaching your central nervous system to fire efficiently under extreme demand. So when you go jogging down the street, you’ll become more competent from running faster once in a while. Okay, um, thank you for writing in.

Brad (35:17):

And now we talked to Ryan Baxter, who’s been a guest on the show and a guest on the B.rad podcast. He’s got great content. He’s a primal health coach in New England and an engineer by trade. And he’s done some amazing quantifiable experiments with his training, with his diet, uh, that everyone can reference for our benefit. And I think think the most profound one was his experiment with as I’ve been experimenting with striving for, maximum cellular energy status at all times. So transitioning away from a devotion to fasting or low carb or keto and going for, uh, a good sensible intake of nutritious foods to fuel his performance and recovery goals. So what he did for all of our benefit was he performed a careful experiment where this guy has written down everything he’s eaten for years, and all the macronutrients put everything into the app so he knows his average daily caloric intake and his carbs and his protein and fat. And then he went on and embarked upon an experiment lasting one year where he consumed an additional 700 calories per day in additional nutritious calories that includes more carbs, more protein, more everything. And he carefully tracked this, and at the end of one year of stuffing his face extra to the tune of 700 calories a day, which is no joke, he had the same body weight and the same body composition, almost exactly the same.

Brad (36:48):

He was, he had gained a quarter pound or lost a quarter pound or something, but essentially nothing had changed. And so it begs the question, where did all those extra calories go to? And arguably they went to improved performance and recovery so that he could get fitter, uh, lift more weight, run faster, perform better without bringing in that extra stress factor of restricting caloric intake in the name of health benefits. So those of us who are putting out a lot of energy into our training protocols, we wanna make sure that we’re getting enough nourishment to perform and recover optimally. And I’m super excited about what I believe is, uh, yet another, uh, a breakthrough or progression in the message and the ancestral health movement, the progressive health movement in general, where we see these benefits, these tools for what they are, the fasting, the keto, the carb restriction.

Brad (37:45):

We see them for what there are, but we have to zoom out, look at the big picture, and realize that these are just tools to achieve a desired benefit. And oftentimes that desired benefit is to extricate oneself from the unfettered access to indulgent foods that we see in modern life. Dr. Elaine Norton makes an excellent case that all metabolic problems can be attributed to energy toxicity, and energy toxicity is simply consuming too much energy and not burning enough. So we have the sedentary patterns of modern life, and we have our ability to indulge in foods day and night with the click of a button, without having to make any effort. And he goes way out onto the extreme where he doesn’t even, uh, you know, distinguish or have tremendous concern on, uh, you know, the quality of the diet or which food you cut back on.

Brad (38:40):

He just says, cut your calories and you’ll get healthier because you’re gonna lose weight and improve your metabolic markers. And that is a true statement. There’s just so much complexity here about what’s sustainable, what’s possible. And I think a lot of the benefit of the ketogenic diet is that it’s easy to adhere to because you do curb your hunger because you’re not spiking blood sugar. And generally, you’re gonna find a lot of nutritious foods when you go keto because you’re gonna be emphasizing, uh, the great animal superstar nutrient dense foods like red meat, like eggs, like oily cold-water fish, and so forth. So, um, what I’m trying to get to here is to not get too muddled in the waters and realize the objective of some of the health practices that you’re undergoing. So if you make a dietary change and now you’re gonna go keto and measure your carbs, or now you’re gonna do intermittent fasting and only eat in that eight-hour window of time between 12 noon and 8:00 PM all those things are helping you extricate from previous patterns that were health destructive or at least less healthy than your new practice.

Brad (39:45):

But then when the smoke clears, we have to realize that these are stressful practices. So fasting, you kick into all these wonderful immune cell repair benefits, but it nevertheless is a stressor to the body, just like restricting carbs, uh, greatly with keto. And so what Ryan was showing with this quantified experiment and what I’m showing from my non quantified experiment, but still enthusiastically consuming way more carbs, way more fruit way, significantly more calories every day. I don’t know if it’s up at 700, but I went on a devoted effort starting in May of 2022 after I was exposed to the message from Jay Feldman energy balance podcast to try and cut back on fasting and eat more food. And now at this age, especially 58, going for high performance in the decades ahead, I contend that I am entirely focused on performing and recovering and performing and recovering and no less authority than Dr.

Brad (40:48):

Peter Attia, author of the widely acclaimed new booked Outlive about longevity and all the things contributing to it. He says that exercise is the single most powerful intervention to promote longevity than anything else. And nothing even comes close. No pharmaceutical, uh, not even a dietary modification. It’s all about building and maintaining lean muscle mass and lean muscle strength throughout life, particularly when you look at the things that trip us up and send us to our demise. And tragically, the number one cause of demise and death in Americans over age 65 is falling. So that is a loss of muscle power, muscle strength, balance, coordination, fitness in general. And then when you fall you oftentimes get bedridden, so then you get in worse shape, and it’s really hard to climb out of this hole, especially when you enter the senior decades. So those who can perform physical activity and are able to push their bodies and achieve fitness benefits will have the longest, most graceful, enjoyable lifespan.

Brad (41:56):

And that is supported by, as Jay might call it optimal cellular energy status. So you don’t have to starve the cells of energy when you already challenge them through devoted training sessions that are difficult and, and, uh, push your body, whether it’s resistance training, sprinting, or a lot of general everyday activity. I also like the great point, uh, delivered by Mike Mutzel on his popular YouTube video which is titled Why I Stop Fasting and What I’m Doing Instead, something along those lines for the title. And he cites research that talking about fasting and all the benefits. Yes, indeed, if you fast for 48 hours, you get an outstanding autophagy benefit. That’s the natural cellular internal detoxification process. The research from respected leaders in the fasting community like Dr. Walter Elango and David Sinclair, another longevity expert. They’re talking about, uh, the renewal and repair effects that occur through fasting or fasting mimicking diets as he calls them.

Brad (43:01):

And, uh, the research shows that your organs will actually shrink in size after a 48 hour fast because they have shed the inflamed and damaged cellular material and will rebuild with healthy new cells prompted by the fasting session, which forces your body to become more efficient and, uh, repair and recycle damaged cellular material in contrast to constantly overfeeding that energy toxicity state where your cells divide more quickly and set the stage for increased cancer risk and things like that. So if you fast for 48 hours, you get these wonderful benefits. But then as Mutzel goes on to say, and he’s a high performing athlete, former elite cyclist, and very much on the exercise fitness scene as well as diet, he says, research reveals that you will get a similarly awesome, powerful autophagy benefit from doing an intense one hour workout. And then he hits you with the punchline, which is, I don’t know about you, but which one would you prefer fasting, starving yourself for 48 hours, or going in the gym and slamming out an hour session to get a similar autophagy effect and a mitochondrial biogenesis effect.

Brad (44:14):

And you’ve heard that term before, or you’ve certainly heard of mitochondria. Mitochondrial biogenesis is the making of newer, more powerful, more efficient mitochondria in the body. Many health and medical experts contend that mitochondrial health is the essence of aging gracefully, and it’s the, the essence of health itself and vitality in the body. So if you can get your mitochondria working better or making more mitochondria, you are getting an awesome health benefit. And mitochondria biogenesis is prompted by starving the cells of energy, thereby forcing them to work more efficiently or make more, uh, make new mitochondria. So that’s the ticket is you’ve gotta challenge these cells, it’s sort of like challenging your bicep to become strong, and then you grow a bigger, stronger bicep. Same thing with the mitochondria. And you can do that through many pathways. You can do it through cold exposure because that is a challenge to the cells, challenging your body to maintain core temperature when you get out of the water.

Brad (45:18):

And then, uh, not eating and then, uh, doing something that’s a vigorous exercise. So they’re numerous pathways, they’re called redundant pathways. Dr. Casey Means uses that term, and I love that. And so the thing to be careful of here is overloading on the stress pathways to the extent that they compromise your performance and your recovery. And of course, we’re not talking about a huge segment of the total population that’s at risk of overdoing it with carb restriction and too much exercise. But for the appropriate, uh, listener, this is a huge insight. And so, uh, I’m gonna repeat that often, that I am entirely 100% focused on performance and recovery in my physical fitness endeavors, to the point of the, the influence of my diet. So I’m not gonna introduce dietary stressors ever again because I do plenty of performance during recovery to stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis.

Brad (46:20):

And of course, I contend when you are directing your energies to fitness improvement that has wide ranging benefits, more wide ranging benefits than cutting back on your calories. You know what I’m saying? You know what I’m saying? Okay. And guess what that whole Ryan Baxter thing was just prompted by me looking at his name on the page, and his commentary for the show was on an entirely different and still e e extremely interesting and important subject. So, he says, in primal endurance, you and Mark drive the point home with making sure you stick to maximum aerobic function, heart rate to promote optimal fat burning, reduce stress, reduce carbohydrate dependency.

Brad (47:04):

As I looked more into breathing during exercise, it becomes clear that another thing plays an important role in whether we are burning more fat or carbs during our aerobic workouts, and that is the amount of oxygen delivered to the muscle. If the muscle is not getting enough oxygen, the muscle will burn glucose rather than fat, because oxygen is needed to burn fat as we know. So if you are not delivering enough oxygen to your muscles, you can be working out at even a comfortable heart rate in the aerobic zone and burning more glucose than you should be. And of course, this, uh, example is illustrated by those who are extremely unfit and metabolically unhealthy, and they will be burning glucose if they get up from the couch and walk across the room, right, because they just don’t have the, uh, metabolic machinery building to, to burn fat. And so how do you get more competent? How do you deliver more oxygen to the working muscles? You improve your carbon dioxide tolerance. This is a subject for an entire show. I did a show on the B.rad podcast about the insights derived from the fantastic book, uh, the Oxygen Advantage by Patrick McKeown.

Brad (48:19):

But if you can minimize your breathing during workouts and during everyday life, by the way, you will improve your carbon dioxide tolerance. And the more carbon dioxide you can tolerate, the more oxygen is delivered to working muscles. This is not just Brad going off on a rant. This is called the BORE effect, which is a fundamental of chemistry. B O H R. The boar effect contends that as you build up more carbon dioxide in the bloodstream, you will dispense more oxygen to working muscles. In contrast, if you suck in, uh, a whole bunch of oxygen more than you need, you will not be building up any carbon dioxide, thereby minimizing the delivery of oxygen to working tissues and muscles. And so what do we do generally speaking in life, is we over breathe as McKeown argues, uh, especially during exercise, we’re customary to just open our mouths and suck in a bunch of air while we’re jogging down the street or while we’re going faster or going slower.

Brad (49:22):

Doesn’t matter. We don’t care. We don’t think about it. I never did think about it myself. I never thought of, uh, breathing as a performance tool. But this new information that’s become very popular, especially with Brian MacKenzie, forming his shiftadapt.com operation and taking people through the gearing of different breathing as they increase the intensity of their exercise, all this new information is really become, uh, prominent in the performances of lead athletes and getting adopted by more and more people. So, the short version of it, as Ryan explained a little bit of the science there, is if you can form a goal to breathe through your nose only as minimally as possible at all times for the rest of your life, that is the key to leveraging the benefits of building your carbon dioxide tolerance and delivering more oxygen to working muscles.

Brad (50:19):

There’s also all kinds of other peripheral benefits for the central nervous system when you get good at carbon dioxide tolerance and, uh, you more likely to stimulate parasympathetic function at rest when you’re breathing through your nose only and taking efficient diaphragmatic breasts, but getting away from this over breathing tendency, which is associated with the stress response. And think about it, when you are stressed, you are taking shallow panting rapid breaths, you are almost hyperventilating when you get to the extreme stress. So we know what hyperventilation is like when you’re in a panic, but down four notches from there is our everyday pattern of just rushing through life, panting, panting, panting, taking in way more oxygen than we need, and thereby minimizing our carbon dioxide tolerance. So again, this is content for a whole show, but it definitely plays in that if you can get better at minimize breathing during exercise, like if you can get by with taking in less air, you will A minimize the stress impact of the workout, and B improve performance by delivering more oxygen to the working muscles.

Brad (51:30):

When I listened to the entire Oxygen Advantage book two times through, I almost couldn’t believe my ears like, this guy’s telling me if I breathe less, I’m going to perform better. But as I learned all the concepts and see the, compelling evidence out there, I have become a big devotee of minimized breathing. And I think about it all day long, and especially during workouts. So, you’ve heard about the per perhaps heard about the shift adapt protocols where you start with breathing through your nose only and then you, uh, the next step is, uh, breathing through your nose and exhaling through your mouth. And then when you’re going really hard and you need maximum, of course, you’re breathing in and out through both nose and mouth, uh, aggressively. So when I’m doing my sprint drills and sprint workouts, what I’ll do is I will start from a nasal breathing foundation.

Brad (52:20):

So I’m breathing through my nose only even as I do pretty challenging drills for 10 or 15 seconds. And then when I’m done with the drill sequence, of course, I will open my mouth, I’ll take a couple big breaths to get the air I need, and then try to downshift quickly back to nasal breathing. So at all times I’m taking in as little oxygen rather than as much as I can. And again, just so you don’t misunderstand, I’m not trying to turn myself red and pass out on the side of the track. So when I’m running a full speed sprint, I’m breathing maximum oxygen that I need, and then just trying to down gear, down gear as soon as I’m done. And then someday, however long that takes, five seconds, 20 seconds, 30 seconds, I’ll close my mouth again and go back to nasal breathing.

Brad (53:09):

So, I encourage you to read that book and maybe go over to the B.rad podcast and listen to my, uh, highlight show, talking about the insights from the Oxygen Advantage, and realize that it actually can improve your performance. And, in a general recommendation here to, to close this topic out and close the show out, uh, I would suggest trying to do those nose breathing workouts, which also correlates with staying under your maximum aerobic heart rate. And it’s a bit of a hassle, especially if you’re not used to it. You might be spewing out a lot of fluid outta your nose and getting annoyed that you can’t open your mouth and just breathe normally. But over time, you’ll get used to it. Your nostrils will get stronger, your airways will get stronger, and you’ll be able to, uh, pedal on down the road or on the exercise bike or jog on down the trail breathing through your nose only.

Brad (54:03):

And it’s a wonderful feeling and it literally minimizes the stress impact of the workout. All right, we got into some major important big picture topics in this show, and I really appreciate you listening. We would love to hear your feedback on the show. So if you can email podcast@bradventures.com and designate your question for the Primal Endurance Podcast, that would be great and good luck out there trained safely, don’t overdo it, and definitely spend some time at primalendurance.fit, checking out the free mini course, and I guarantee you’ll be satisfied when you enroll in the Primal Endurance Mastery course.

Brad (54:47):

I hope you enjoy this episode and encourage you to check out the Primal Endurance Mastery course at primalendurance.fit. This is the ultimate online educational experience where you can learn from the world’s great coaches and trainers, diet, peak performance and recovery experts, as well as lengthy one-on-one interviews from several of the greatest endurance athletes of all time, not published anywhere else. It’s a major educational experience with hundreds of videos, but you can get free access to a mini course with an e-book summary of the Primal Endurance Approach, and nine step-by-step videos on how to become a primal endurance athlete. This mini course will help you develop a strong, basic understanding of this all-encompassing approach to endurance training that includes primal aligned eating to escape carbohydrate dependency and enhanced fat metabolism, building an aerobic base with comfortably paced workouts, strategically introducing high-intensity strength and sprint workouts, emphasizing rest, recovery, and annual periodization, and finally, cultivating an intuitive approach to training. Instead of the usual robotic approach of fixed weekly workout schedules, just head over to Primal endurance.fit and learn all about the course and how we can help you go faster and preserve your health while you’re at it.