Mark Sisson On The Origin Of The Primal Endurance Movement

In this episode, Mark Sisson and I talk about the origin of the fat-adapted athlete approach in contrast to the carb-dependent endurance athlete, which represented our main experience in endurance sports for those early years and decades.

This show will give you a nice overview of the rationale and the benefits of transitioning from being the typical carbohydrate dependent endurance athlete to being a fat adapted athlete, and how you can do that through dietary modification and training modification. Mark shares how he feels about reconciling his longtime passion for endurance training and elite competition with his Primal living path and his recent breakthroughs in his endurance training philosophy. You will also hear us discuss the benefits of being fat adapted and the drawbacks of training in an inflammatory, oxidative carbohydrate dependency pattern

TIMESTAMPS:

Brad is back with Mark Sisson to talk about the origin of the fat adapted athlete approach. [00:01]

What is going on these days with endurance training theory compared to 20 years ago? [01:42]

What kind of diet works best away from training? By cutting out carbs and cutting way back on sugars and starches and grains, Mark is a super fat-burning machine. [07:03]

Sugars are more than candy. There are tremendous quantities of sugars in fruit juices, pancakes, waffles, pasta, cereal. [09:21]

How does one dial this in with a primarily approved eating pattern as well as a sensible endurance training? [11:14]

What is the right amount of carbs? You need intuitive knowledge regarding your training program and your daily life. [15:55]

To do this right, you need to go back to a strong aerobic base. [21:22]

Form and strength training are important to plan out your program. [24:31]

The importance of rest seems to be overlooked in many areas of training. You can’t train on someone else’s schedule. [29:23]

LINKS:

- Brad Kearns.com

- Brad’s Shopping page

- PrimalEndurance.fit

- PrimalEndurance Facebook

- How to Improve Your Triathlon Time

- Primal Endurance book

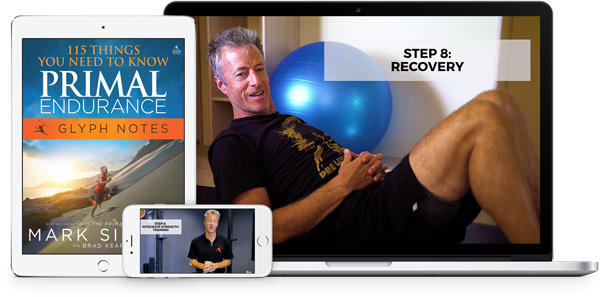

- Primal Endurance Mastery Course

TRANSCRIPT:

Brad (00:01):

Welcome to the Return of the Primo Endurance Podcast. This is your host, Brad Kearns, and we are going on a journey to a kinder, gentler, smarter, more fun, more effective way to train for ambitious endurance goals. Visit Primal endurance.fit to join the community and enroll in our free video course. Well, I think it’s time to hear from the show that started it all, the very first episode of the Primal Endurance Podcast and the special guest, none other than Mark Sisson. This is a great conversation where Mark talks about the origination of the, uh, the fat adapted athlete approach, in contrast to the carb dependency endurance athlete, which represented our main experience in the endurance sports, uh, for those early years and decades. So I think you’re gonna get a nice overview of this important transition, the rationale and the benefits for transitioning from the typical carbohydrate dependency endurance athlete to becoming a fat adapted endurance athlete. And how you do that through both dietary modification as well as training modifications. So putting it together, making the right training decisions and the right eating decisions. Let’s hear from the man himself, Mark Sisson,

Mark (01:26):

What do you know about that? Here we are again, Brad,

Brad (01:28):

We missed you, man. It’s been a while. And we’re here to talk about one of our favorite topics, especially because this book project has been in the works for a long time. Uh, primal endurance I’m referring to. So we’re gonna talk about endurance training.

Mark (01:42):

Yeah, it’s sort of my new favorite topic because you know, for a long time it wasn’t my favorite topic. Well, let’s, let’s go back even further. It was my favorite topic for most of my life, and then it wasn’t my favorite topic when I started looking into chronic cardio and all of the damage that I’ve been doing to myself. And then I realized, you know what, so many people are into this concept of maximizing endurance. Maybe there’s a right way to do this. Maybe there’s a way to go about training that doesn’t break the body down, that does give you the results that you seek that is fun to a certain extent. And that, um, you know, and, and, and fills in all of those boxes that we used to check off and go, Well, forget about that. I’m not gonna do that.

Brad (02:20):

Well, you’re right. It’s, the sport is getting more and more popular for years and years. It hasn’t gone away and it’s really transitioned from kind of a very niche and highly competitive sport. Like in our time, there wasn’t a lot of, uh casual,

Mark (02:36):

We talking about triathlon,

Brad (02:37):

Triathlon and marathon horror. Yeah, I

Mark (02:39):

Mean, I mean, all these sports, all these enduring sports. So yeah, we’re talking about marathon, we’re talking about triathlon, we’re talking about cycling, long distance swimming. We’re talking about Orientering and any of these events that require, you know, that you dig deep for long periods of time to perform well.

Brad (02:55):

So it’s been such a long time since we were pulled to what was going on. And now we’ve kind of jumped back in, seen what’s transpired in the last 20 years in terms of training methods and hot topics and all that. What’s your take of kind of where things are today with endurance training theory and all that?

Mark (03:16):

Well, I’m very excited because, and I think that my new excitement comes out of having stepped back so far away from it that I I I’m not, beholden to some of the old precepts and some of the old dogma that you know, that that burdened endurance trainers for so long. The concept that more training was better, the concept that, you know, you had to eat a lot of carbs and maintain large glycogen stores in order to perform well. Having stepped back from that and having approached this whole, uh, challenge from a new point of view, which was, okay, if the goal is to perform well in races, and in the process to achieve my ideal body composition, in the process to never get sick and not fall apart from the training, if the goal is to, to have this, um, endurance part of my life be a major positive factor in my life and not one that detracts my life, what’s the way in which I can become lean and race fit with the least amount of pain and suffering and sacrifice. Having used that as my sort of guiding principle, like what’s the most benefit we can get with the least amount of input?

Mark (04:33):

Um, it allowed me and you and, and those of us who are researching on this side to step back and go, Wow, this is, this is really a complex equation. And some of the new revelations that, that arose. For instance, I can become good at burning fat during racing, um, by shifting the way I eat when I’m not racing or when I’m not training in. It’s crazy to think that you can train yourself to become a good fat burner, largely from just shifting your diet and not really paying that much attention to how much training you’re actually doing that, that a lot of this repositioning of fuel happens as a result of how you eat, not as a result of how you train. That was huge for me. Um, certainly understanding that, um, that what falls apart in races, whether you’re a citizen athlete trying to complete a 5K or whether you’re an elite athlete trying to complete a a a, an elite marathon or a work class marathon or triathlon, it’s form that falls apart.

Mark (05:31):

And when form falls apart, that’s when the wheels really do start to come off. That’s when the wall, you start to hit the wall. Uh, and there are ways that you can train against that in the gym that don’t even look like traditional training of putting in more miles and doing intervals and all of the things that we assume we had to do. But there are things that you can do in the gym, lifting weights under certain conditions that will, uh, improve your ability to maintain and hold form when the, um, uh, when the stuff hits the fan when you’re up, you know, on that third climb, um, of, uh, 3000 foot gain over the next, uh, couple of miles. Uh, or when you’re at the 20th mile of the marathon or you’re in Boston trying to go over Heart Bay Hill when form when you can consistently whole form because of the training that you did in the gym using weights that had had really very little to do with actual miles that you put in. That’s really exciting to me to think that we can, that we can achieve some of these breakthroughs, um, a lot easier than we used to assume we had to do.

Brad (06:30):

Right. So if we had to do it over again, what you’re saying, you’ve covered a lot really quickly there, so we’ll, we’ll, we’ll back up and get into each of these things individually, but the old school approach of just going out there and putting in the miles and basically crossing your fingers hoping you wouldn’t get sick, injured, and that you could make it through these grueling events, relying on sugar and additional ingestion of performance aids and all those things is now being reconsidered by, let’s start with your actual diet during away from training.

Mark (07:03):

Well, my actual diet away from training has been an evolution over the years with my intention being that I did want to, I, I still wanted to maintain lean body mass. I wanted to have the lowest body fat possible and carry around the least amount of excess weight possible. I want still to have as much energy as I required to get through the day and in cutting out the carbs starting 15 years ago. But certainly in the last 10 years in cutting the carbs way back and cutting out the sugars and in the starches and the, uh, in the grains, I realized that I was becoming really good at burning fat and how that manifested itself to me, even though I wasn’t racing anymore. And even though I wasn’t really training that hard, I found, for instance, that I could wake up in the morning and not be hungry.

Mark (07:49):

And that was huge for me because I used to wake up ravenous and had to have breakfast every day. Well, just to be, to be able to wake up and not eat until noon or one o’clock on a normal day, told me I’m becoming good at burning fat. Now how do I apply that to my training? Or how do I apply that to, um, some, some performance aspect of life? I can go on a two hour hike and hike pretty hard and not have to eat before the hike, not have to eat during the hike, not have to eat after the hike, and know full well during the hike that I’m burning largely, predominantly carbohydrate, excuse me, fat. And I’m not burning carbohydrates and I’m not dipping, uh, into my glycogen stores and I’m not hitting the wall. That’s just a small subset of all that is possible when you become better at burning fat and less reliant on glycogen stores to keep you going from one training day to the next or from one race to the next.

Brad (08:44):

And you didn’t even mention the health benefits, like the protection against oxidative damage that comes when you’re burning sugar and consuming a lot of sugar. So when you get fat adapted, not only do you have better energy to stay, to break through past the wall, but you’re protecting your health and you’re minimizing your risk of heart disease and, and those kind of things that have been now tied to, and you’re one of the guys that have been on the forefront of this, that extreme chronic endurance training is directly associated with heart disease. You’ve put articles up on that and it’s something that requires an awakening for anyone who thinks that they’re running their way or cycling their way into health and disease protection.

Mark (09:21):

Yeah. You know, you talk about the inflammation thing and we assume that it’s usually the excess miles that are causing the tremendous amount of oxidative damage and, and breakdown and inflammation and injuries. And, and that’s true. They are. But, uh, we should not overlook the fact that it’s the, the sugars that we have that we traditionally took in, in all of this training that just notched that whole ramped that whole inflammation process up, uh, a degree. I mean, it was now, it was not just a miles, but it was a combination of the miles and the sugar based diet. And when I say sugar, I’m talking about not just the sugar and a bowl of sugar and bag of Skittles, but I’m talking about, I’m talking about the sugar in tremendous quantities of fruit juice that I was consuming in the, in the pancakes and waffles, and pasta and cereal and rice that I was using to, to be able to restore glycogen on a day to day basis.

Mark (10:19):

All of those things certainly contributed to a tremendous increase in inflammation that went away or subsided Dr. Dramatically when I cut back on all of those, um, unnecessary carbohydrates and became better at burning fat and, um, started to, to enter this situation where we call it a fuel repartitioning, where I’m relying less on glucose and relying more on fat, and I’m timing my work output to the extent that I’m not overdoing it. I’m not tapping into not going glycolytic and tapping into glycogen stores that often, but I’m managing my output, my, my work output so that I am mostly burning fat. It’s a beautiful thing, but it takes, it, it’s a skill that, that I’ve developed and that I want to teach to other people who want to, you know, learn how to optimize their health and maximize their performance.

Brad (11:14):

So what’s cool now, and this is dating back to, uh, guys like you and the, and the early primal paleo guys getting the message out there, now it’s what, seven years, seven years ago that Primal Blueprint came out. It’s, it’s a hot topic. The, even the endurance athlete is aware of this low carb endurance movement, but to me, it seems like there’s still some confusion and misunderstanding and complaining from the average athlete that this is really troubling to eat in this manner. I don’t have the energy to do my workouts. And just wondering just how to approach this in a way that’s gonna be easy to implement or transition out of that high carb burning, high carb eating pattern that most endurance athletes have been locked into.

Mark (12:00):

Well, and that’s an important point to make because there are ways that you can mess this up. There are ways that you can sort of buy into the concept of low carb eating and low carb training and then screw it up royally because you train too hard, too often at the wrong periods of time. When you decide to embark on a, uh, a program of training to compete in an event or training to complete some bucket list item that you have on your list. I don’t, I really don’t care what it is. And you’re gonna screw it up by getting back into an overtraining, sugar- based strategy. So it’s incumbent upon one who who likes to, to embark on this low carb, uh, training strategy to kind of understand how the body works and understand the elements of breaking down a race into its component parts.

Mark (12:48):

You know, how do I, how do I train my muscles in a gym to be able to maintain power and hold form over time? How do I, um, maximize my aerobic efficiency, not by going hard all the time, but almost by, by going less hard most of the time so that I increase the efficiency, I increase my abilities, my body’s ability to burn fat at a particular level of output, and over time I’m able to output a greater wattage, if you will, at that same, uh, level of fat burning. And these are, these are critical components to put together in your training program. And if you don’t understand how the body works and if you don’t get that, there are times at which to go easy and times at which to go hard. There are times where you don’t want to eat and times when you do wanna refill the glycogen stores, you can get yourself in trouble and you can, you can, you know, fall apart or, or at least not maximize your performance and perhaps compromise your health.

Mark (13:45):

So what we’re trying to do here with this new book and with this whole strategy is to give you all of the basic building blocks to put together a training program that works for you in the context of whatever event you’re trying to do. And I think that the beauty of this book is you’ll see exactly, at what you know how to put these things together and personalize a program based on your goals and based on your assessment of where you are in your, your physical life right now and in your family life and your work life,

Brad (14:13):

Right? So we gotta be careful with some of this terminology that can be confusing. And when you hear low carb and endurance, those are sort of diametrically opposed in many ways. So what we’re really talking about is your own thing is the primal style eating pattern, which might be low carb in comparison to the disastrously excessive carbon tank of standard American diet. But as an athlete, hey, refilling glycogen tank, of course you wanna do that and it doesn’t take that many carbs. So can you get a little specific about how does someone dial this in with a primaly approved eating pattern as well as sensible endurance training? Right.

Mark (14:55):

Well, you dial it in through trial and error like you do with in any aspect of this, this N equals one experiment that we talk about in primal living. You dial it in based on the understanding that you are going after an appropriate amount of carbs, not an excessive amount of carbs. So for the longest time since I started working with Olympians in I wanna say 2000, we started talking about reducing the carbohydrates in the diet, reducing the excessive carbohydrates in the diet, and only using what was appropriate with the understanding that, you know, the, the liver only holds a hundred, 120 grams of glycogen. The muscles in the rest of the body hold maybe 400, 450 grams of glycogen. And those 450 grams never dip below, say 150. So you really only have like a 300 gram window that you’re gonna fill up even when you carbo load.

Mark (15:55):

So it doesn’t take 700 grams of carbohydrates over the course of a day to carbo load, or it doesn’t take some inordinate heaping mound of, of spaghetti topped off with some bread and some beer to top off carbohydrate stores. It just takes, uh, another half a sweet potato and maybe a couple of spoonfuls of rice. So we’re talking about an appropriate amount of carbohydrates that would top off glycogen, but don’t interfere with your renewed and, and recently acquired ability to become good at burning fat and act to access stored fat. And I think that’s an important, you know, point to, to sort of raise immediately, which is we, I talk about low carb in the context of what I used to eat, which was thousand grams a day of carbohydrate or whatever it may be, 250 to 350 grams of carbs a day is, is low carb for a lot of elite athletes because they become so good at burning fat that they derive most of their energy from their from their body fat or from the fat on the plate of food while they’re training relatively hard. And they don’t really need to dip into glycogen that often. And when they do, they replenish it very quickly with minimal amounts of added carbohydrate.

Brad (17:05):

It seems like could be as simple as if you’re taking in extra carbs, maybe you have excess body fat, and if you’re not getting enough carbs, maybe you’re not recovering from workouts and it doesn’t seem as hard. I know there’s a lot of people that like that anal calculation where you can go and, and type in how many calories you burn, but could it be characterized in simple terms where someone could just dialed in an intuitive manner rather than using a calculator?

Mark (17:33):

Well, absolutely. You dial it in intuitively. Um, the, uh, and, and you know, there’s a fudge factor either way. If you’re off by 50 or, or whatever grams on a daily basis, it’s not gonna be the end of the world, but that you can most assuredly you can dial in the appropriate amount of carbs for you, not just based on a daily intake, but based on from day to day what your work, uh, looks like or, or has been. In terms of, if you know, did you do an interval set today and based on that interval set, did you carbo load last night, slightly in order to prepare for this interval set that you knew you were going to do today, that you knew you were gonna go glycolytic and then after the interval set was over, if you don’t have anything pressing to do in the next 24 hours in terms of athletic output, you know, maybe you reduce carbs even lower.

Mark (18:23):

Maybe you use this as an opportunity to promote mitochondrial biogenesis, build more mitochondria, become better at burning fat. But what you didn’t want to do was you didn’t want to come into today’s glycolytic intense, interval session with a depleted glycogen tank. So it’s just, it’s getting this intuitive knowledge of what your training program looks like and how it varies tremendously from day to day based on what you have planned, uh, what the rest of your life looks like in terms of your work, your family, um, and, and you know, vacation or hobbies or whatever. And understanding kind of, again, intuitively how much fuel you need to get through the next period of time.

Brad (19:05):

And it seems like your appetite can be a wonderful guide here where you, you get into a chronic training pattern, you’re gonna be hungry all the time, you’re gonna be hungry for carbs, you’re gonna be adding excess body fat, or at least not able to take it off. And if you’re training sensibly and balancing stress and rest and regulating your insulin production by falling a primal style eating pattern, your appetite’s gonna stabilize. Or if you did a big hard uh, workout day, you’re gonna be hungry for that extra half sweet potato or one and a half or whatever it is. Yeah,

Mark (19:36):

That’s, it really, uh, gets down to your ability to listen to your body and to heed the warning signs and heat the signals. And if you’re hungry, it’s, it’s, it really is. If you’re training appropriately, your body will tell you when it’s time to eat and your body will not give you an excessive appetite when it’s not time to eat. If you’re, if you’re doing this the right way, if you’re doing it the wrong way. And if you’re, if you’re not paying attention to signals, it’s quite likely that you’ll be hungry a lot more often that you’ll be overeating carbs because that, that’ll be the signal that you’re driving to your, to your body. And, and that’s where you get into you know, this what we call the, this no man’s land of, well, I’m out there working hard, I’m training hard every day, but I’m not improving. I’m not losing weight. What’s going, what’s wrong with me? Well, what’s wrong is, you know, this is an undertaking that requires that you sit down and figure out who you are, what your goals are, and then plot a strategy. You can’t just go into it saying, Well, I’m gonna do more miles and I’m gonna eat a lot of carbs and I will get faster. Cuz it’s, it’s quite likely, you know, you could get faster, but you could also fall apart like so many of us did for so long.

Brad (20:43):

Okay. So maybe the listener is a little tiny bit frustrated knowing they have more potential and might be able to feel better, drop a few extra pounds of excess body fat. So on the diet front, just to kind of summarize, then I got a couple other topics we want to get into here, but cut the grains and sugars right, and the sweetened drinks and all the fuel that in some cases they’ve been told to consume as endurance athletes. We’re gonna try to cut that stuff out gradually if necessary, but cut it out. And then on the training side, if we’re gonna say, Hey, I’m gonna eat primal aligned pattern now with the training, how are we gonna stay away from those chronic patterns?

Mark (21:22):

Well, the first thing is that you almost invariably have to go back to building a strong aerobic base. If you’re gonna do any kind of endurance activity, you, you need a strong aerobic base. You need to be efficient in that zone where you’re taking an oxygen, you’re, you’re combusting the fuels appropriately, presumably you’re burning more fat. And in order to do that, the real challenge for most people who are training is to stay below that zone, stay below that aerobic maximum zone to the point that it’s almost uncomfortably slow. And, and yet what we know from now 20 years of experience in watching athletes who have, who’ve embarked on this strategy is that over time your efficiency improves. You become better at generating power and holding form and your aerobic efficiency improves to the point that you can run a minute, a mile faster or ride the bike two miles an hour faster at any given heart rate. And the reason is you’re better at burning fat and you’re less reliant on glycogen, you’re better at sparing glycogen. It’s really that simple.

Brad (22:35):

I mean, isn’t that the order of finish almost when you stand at the finish line of a marathon, is the guy who’s the best at sparing glycogen is out front?

Mark (22:43):

That’s pretty much it. That’s pretty much it. The guy, the guy that’s exactly right. The guy who has the most amount of glycogen left in his tank is probably the guy that won because everyone else had exhausted theirs and hit the wall. And for those guys, by the way, hitting the wall means going from running 4:48 a mile to only running 6:10 a mile for the last three miles. But that’s enough to, to determine the outcome of the race.

Brad (23:06):

The other relevant thing here is an anyone knows who’s tried to pursue an endurance goal, it’s tough. The training is tough, it makes you tired, it suppresses your immune function so you get sick, there’s a high injury risk and all these things that endurance athletes deal with. But when you’re in that aerobic zone, the stress impact of the workout is so much lower. And so you can progress without interruption. That’s why you had your athletes when we were back on the Pioneer Professional Triathlon team, you were begging us to slow down in the early months of the season so that we could build to something respectable before putting the heat on and fine tuning whatever. Whether we’d built a Ferrari engine or a a Volkswagen engine was dependent upon how that base looked.

Mark (23:51):

Well and that required that we sit down at the beginning of the season and literally plot out a 12 week season. So we picked our races at the end of the season and, and then worked our way back into you know, when we were gonna build a base and at what point we were gonna introduce, um, breakthrough workouts that we called them. And then at what point we were gonna introduce C races and B races as part of a training strategy. These weren’t all out of efforts, but they were races that we would get into to test, you know, kind of where we were. But in those days, we really only picked a couple of races toward the end of the season that were the ultimate expression of the entire year’s worth of training.

Brad (24:31):

Right. So peaking is important. Periodized training is important. Yeah. And that brings me to, you made a comment earlier about getting in the gym and doing those strength and those mobility exercises that translate directly into holding your form when the body starts to break down at the end of the race. So when it’s time to throw in those high intensity sessions like sprinting and, and targeted strength training, how does that fit into the picture?

Mark (24:58):

You can do strength training at any point in time, but ideally when you pick out a 12 week or a 16 week training program that’s geared toward getting you to a major event at the end of the season. Ideally, I think you do a lot of that maximum overload training in the early part of your training. You develop some of the, the motor skills and the neuromuscular patterning and the deep, deep fiber recruitment early on, and then do it maybe less frequently, but not eliminate it entirely, just do it less frequently as the season progresses.

Brad (25:33):

And you said maximum overload, and that’s an advanced strategy advocated by the Los Angeles trainer, Jacques DeVore that he used withTour de France cyclist, David Zabriskie. We’re gonna get into great detail on that in the book. But basically, and, and, uh, astute listeners have heard Kelly Starrett talk about this a lot too. When you put yourself under load in the gym with, for example, doing a weighted squat, you’re doing something that doesn’t easily come out on the road. And that is, let’s say, identifying your weaknesses when you’re at that maximum point when you’re tired at mile 20 of the marathon or late in the bike ride of the Ironman race. But when you go in the gym and build the proper form and, and function and identify your weaknesses and work on those, that will translate directly into long slow performance out on the endurance race course,

Mark (26:25):

It’s a little bit difficult for the average person to grab this or grasp this because it doesn’t, it, it doesn’t make sense necessarily intuitively. But the fact is that holding form, you know, is, is a, uh, is a, it’s a pattern that you, you have a certain way in which you, your leg turns over or on the bike or on sprinting. So it may be that on that, like we say on that third climb of a mountain, normally you’d fall apart because you don’t hold form anymore. You don’t have the strength, you still have the aerobic capacity sort of throughout your body, but you haven’t developed the strength to keep that power through that third climb. Yeah.

Brad (27:03):

Have you ever slowed down because you lost your breath in, in a marathon or Triathlon?

Mark (27:07):

Never. Okay. It’s over

Mark (27:10):

Finished. Never the best marathons I ever did. I never finished out breath. And that’s, I think that’s even, you know, even with a sprint finish. And that’s, I think very, um, you know, indicative of what happens because it’s, it’s the, it’s the muscles that give out long before the, the cardio or the aerobic system that gives out for most people. And that’s, that’s really, you know, that that’s what happens as a result of, of not training those deep, deep fibers and recruiting those fibers to hold form over time. So, uh, so, and by the way, it didn’t isn’t just with, with endurance athletes. I mean, this could be a 400 meter runner who, who, you know, it’s a largely anaerobic event, 44 seconds or whatever, but if they start to lose form in the last 60 meters, they’re gonna get beaten. And it’s not that they’re out of breath. They’re, they’re out of breath, but their breathing isn’t gonna, isn’t gonna be the difference in the outcome. It’s whether or not they can hold form through the finish line.

Brad (28:04):

And even, even at the starting line, if you have muscle imbalances, cuz all you do is run and you have poor hip flexer, uh, function and weak and glutes and, and things that aren’t working right, you’re just not only losing performance, but you’re increasing your injury risk. So you can get some stuff done in the strength training. It doesn’t have to be the fancy maximum overload prescription, but just doing, let’s say the primal essential movements for endurance athletes can go a long way.

Mark (28:31):

I would argue that I was onto this early in my racing career and I lifted weights as a marathoner, and as a result I probably carried 10 extra pounds of body weight. Um, I was five 10 and I weighed 145 when everyone around me who was also five 10 was weighing 135. And this is in the seventies. Um, and I, because I, I was intuitively aware that by increasing my strength that I was going to be able to hold form a little bit better, uh, then just putting miles in and hoping that I could suck it up and, and, and hang in there aerobically. And I go back over the results and I, I wasn’t that genetically gifted an athlete that I should have been an elite runner. I just worked really, really hard. I did put in too many miles, uh, but I also feel that, um, I benefited from the time I spent in the gym lifting weights as well. Mm-hmm. <affirmative>,

Brad (29:23):

One thing that’s a little, uh, irritating to us, I’d say is we we’re looking around and seeing what kind of prevailing, uh, fads there are now in the endurance scene. And there seems to be some disparate camps. Some people are advocating or emphasizing the aerobic is everything. And then other people are saying that, hey, high intensity is kind of a hack where you can go in and do these short duration really, really strenuous workouts. And that has the same translation to a long distance run because you’re fatiguing your muscles in that manner. But one thing that seems to be overlooked still decades later is the importance of rest.

Mark (30:02):

Yeah. Well, first of all, to your point about, you know, you can, you can hack this by just doing work in the gym, I would say you can’t. I’d say the, the, the ultimate realization is that if you’re gonna run distance at some point you have to run some distance. If you’re gonna race a marathon at some point you have to put in some long runs. And you can’t just do that doing burpees and weighted squats in the gym. Uh, maybe on a, on a, you know, ballroom bet you can finish a marathon, but you certainly can’t maximize, uh, your potential doing that. Uh, but to rest, uh, the, that may be the single biggest factor missing in most training programs today. This, this, we’ve talked about it and we’ve you know, we almost joked about it over the years that, well, yeah, we should probably get a little bit more rest because, you know, the body doesn’t improve by training.

Mark (30:54):

It improves by resting, it improves by the recovery. You break it down in training and then you rest to recover. Well, it may be that, that even more rest is necessary than we’ve been giving it credit. And I know for myself that o as I’ve gotten older, I can still do the difficult workouts. I just can’t do them as frequently. I take, it takes time for my body to recover, to repair, and to regenerate itself from the, the work that I did in the hard workout. Um, and maybe whereas I used to be able to go day, you know, from one day to the next, able to pick it up and go out and run hard again. Now it’s, you know, now it’s, then it was every two days and that was every three days. And now it might be once or twice a week that I can do a hard workout, but I can still do the workout as long as I give myself the opportunity to rest.

Brad (31:42):

Right. We were just reminiscing about this at lunch today and talking about in my time when I was racing on the circuit and you were coaching me, and I was, uh, frustrated because I’d go and train with the top guys like Mike Pigg and I had no chance of hanging with his superhuman training schedule where he went out day after day after day and just, and just hammered it. Yeah. Oh, all, all day long. Yeah. From sunrise to sunup and you said, Hey, why don’t you just do his best workouts, his best bike ride, his best run of the week. And it took the pressure off me right away to try to, you know, accumulate all this volume that’s highly individual what a person can handle, but instead focus on that breakthrough workout strategy you call it, where you just measure yourself by your best efforts of the week. And if you’re feeling tired or wanna modify your training patterns and be more intuitive about it, you just throw in more rest and in many cases improves performance.

Mark (32:38):

Well, yeah. If you take a step back and you go, Why am I doing this? Am I doing this to accumulate miles or am I doing this to become a better endurance athlete? And if the answer is the latter, I’m doing this to become a better endurance athlete, then I really don’t care how I get there. And if I, and if I get there by doing less aggregate work and putting in fewer miles, but I’m much smarter about when I choose to do my workouts, I’m much smarter about how much time I rest in recovery in between. I’m much smarter about how I eat than, than that to me is a, is a winning strategy. That’s a much better strategy than just, okay, I put in a lot of miles, I ran as many miles as his other guy did. How come I’m not racing as well as he is?

Mark (33:17):

Well, you got a different body, you’ve got a different mix of fuels that are going into your system. You may wait, uh, wake up on the wrong side of bed one day and not feel great when he feels great or vice versa. You’ve, you, you know, you can’t race somebody else’s program. You have to or, or train somebody else’s program either. You have to, you have to train according to your own body type, your own goals, your own objectives, your own background, your own diet. And back to, you know, why we did this book, this book is to give the citizen athlete and the elite athlete the opportunity to kind of understand how his or her own body works and then how to craft the perfect training strategy.

Brad (33:56):

Mark. I think that serves as an awesome sneak preview of Primal Endurance coming out in the fall of 2015. So for now, that was a great show. Thanks for listening to the Primal Blueprint podcast. This is your host, Brad Kearns, signing off from Malibu.

Brad (34:14):

I hope you enjoyed this episode and encourage you to check out the Primal Endurance Mastery course at primalendurance.fit. This is the ultimate online educational experience where you can learn from the world’s great coaches and trainers, diet, peak performance and recovery experts, as well as lengthy one on one interviews from several of the greatest endurance athletes of all time, not published anywhere else. It’s a major educational experience with hundreds of videos, but you can get free access to a minicourse with an ebook summary of the Primal Endurance approach and nine step by step videos on how to become a primal endurance athlete. This mini course will help you develop a strong, basic understanding of this all encompassing approach to endurance training that includes primal aligned eating to escape carbohydrate dependency and enhanced fat metabolism, building an aerobic base with comfortably paced workouts, strategically introducing high intensity strength and sprint workouts, emphasizing rest, recovery, and annual periodization. And finally, cultivating an intuitive approach to training. Instead of the usual robotic approach of fixed weekly workout schedules, just head over to PrimalEndurance.fit and learn all about the course and how we can help you go faster and preserve your health while you’re at it.