David Epstein: The Sports Gene Book and The Fascinating And Misunderstood Role Of Genetics In Sport

It was a pleasure to connect with the legendary author and investigative journalist David Epstein (who wrote one of my favorite books ever, The Sports Gene) for this episode!

Our conversation ranges from the validity of the 10,000 Hour Rule (you’ll hear David dispel the accuracy of the science behind the concept) to the role our genetics play in sports and performance to the concept of practice variability, and David also shares that he’s looking at writing a book on the specialization in youth sports.

TIMESTAMPS:

David Epstein is an investigative journalist reporting many aspects in the sports world including the role of genetics in sports. [00:27]

If you spend 10,000 practice hours on something, can you become a master at it? [07:09]

There is a concept called practice variability which is not focusing on just one skill. [11:52]

Genetics plays a big role in high level athletics. Some people have a compulsive desire to train. [16:30]

Many people become afraid to go against the traditional approach to training. [27:16]

When we see these exceptional feats in sports, we assume it is their natural God-given gift that allows them this performance. Not so simple. [29:37]

Usain Bolt’s training has been varied. There are no secrets or templates. [30:17]

Epstein, while investigating doping in the sports world, found he had to deal with much controversy. [38:28]

Dave is looking at writing a book on the specialization in youth sports. [46:21]

LINKS:

- Brad Kearns.com

- Brad’s Shopping page

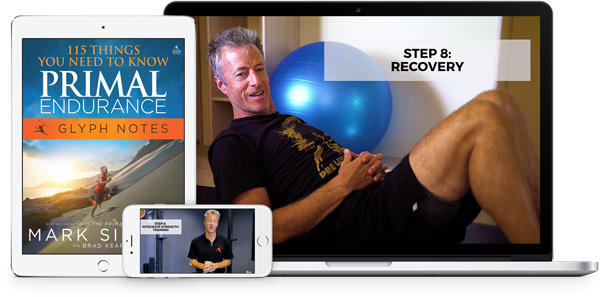

- PrimalEndrance.fit

- The Sports Gene

- Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World

- ProPublica

- DavidEpstein.com

- thompsonriverranch.com.

TRANSCRIPT:

Brad (00:01):

Welcome to the Return of the Primal Endurance Podcast. This is your host, Brad Kearns, and we are going on a journey to a kinder, gentler, smarter, more fun, more effective way to train for ambitious endurance goals. Visit Primal endurance.fit to join the community and enroll in our free video course.

Brad (00:27):

Hey, listeners, what a pleasure to connect with legendary author David Epstein. He wrote The Sports Gene several years ago, and that’s what I interviewed him about. One of my favorite books ever, A deep account of the role of genetics in sport with especially highlighting our widespread misconceptions and misunderstandings about the role of genetics in sports. How could I not love a book that has one of the chapters titled The Tale of Two High Jumpers? And in this tale of two great high jumpers, Donald Thomas from The Bahamas and Stefan Holmes from Sweden, Epstein tells a colorful story that pretty much destroys the widely touted 10,000 hour rule that you have to put in zillions of hours of practice to become,, an expert or an elite at something. And people still banter that about as a fact of life when it’s been widely discredited by elite researchers and investigative journalists like David Epstein.

Brad (01:34):

And he will talk, uh, enough about that. He will get into detail on the fascinating aspects of the sports gene. But since then, he’s gone on to write another, number one bestselling book called Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World. And this is a great contribution to modern culture because for so long, especially in the academic realm and the messaging that we’ve dispensed to our kids and the youth of the world, that we have to become highly skilled in a very niche area of interest. And that is the secret, that is the path to a rewarding and meaningful and stable and secure life. And people like Epstein are looking at the tremendous progress of culture and information technology and exchange of information on the internet, and proposing that this may not be the ideal way to approach the challenge of how to make your way in life.

Brad (02:36):

So it really opens up the conversation to people to look to a more natural intuitive and perhaps, roundabout path to where they end up in life rather than narrowly focusing. I especially appreciate this message when I’m talking to my own kids because they get so much programming about, oh, political science, that’s your your major. What are you going to do with that? Is always the follow up question from adults, and it’s time to knock that shit off and realize that, um, because the future is so fast moving, we do not have that paved in Stone Path as we may have had in the old days, starting with the Industrial Revolution where your aspiration is to, uh, get a job on the assembly line in the factory, and you’re gonna be putting doors on cars for the rest of your life.

Brad (03:27):

And isn’t that wonderful? Oh my gosh, things have blown up now. And that was my little account of Range <laugh>, because we’re gonna talk entirely about the Sports Gene, since this interview predates that. He’s also done some incredible work Epstein has on the website ProPublica, which is a wonderful portal for long form investigative journalism, indeed, the Lost Art of Modern Culture, modern Society, and modern Internet communication. But he did an amazing investigation of the doping allegations leveled at Elite Track and Field coach Alberto Salazar. So, if you’re sick and tired of soundbite headlines and you want to enjoy some real journalism, you can go over to ProPublica and look at Epstein’s work, especially on that area of tremendous interest to me. I just learned so much. And, you also kind of get a sense of what investigative journalism is really all about and the people that are really deep in there.

Brad (04:28):

Another cool thing about Epstein is he was a high performing athlete in college in 800 meters. So, he writes about athletics, he writes about the role of genetics in sports, but he has that deeply immersive background knowledge as a participant rather than just a guy on the sidelines with a tape recorder. I think you’re gonna love this interview and hopefully inspire you to look at some of the great content from Epstein. He’s got some popular Ted Talks. If you go to david epstein.com, you will be able to connect with all his great work. Enjoy welcome listeners. And after a year of trying and admiring from afar, I have finally secured the incredible interview guest of David Epstein, author of The Sports Gene, and many other excellent articles and stories, uh, in the realm of sports and research. And you’re into all kinds of stuff, huh. Dave?

Dave (05:20):

I am. And, and first off, I apologize it took so long to get me on here. I didn’t expect anyone other than like my mother’s book club to read my book. And so I wasn’t prepared for sort of the deluge of, of emails. So I appreciate you following up.

Brad (05:33):

Well, I think it’s, I think undoubtedly the, you know, the seminal book on sports and genetics that’s ever been written, I don’t think anyone would argue that, especially you or your mom,

Dave (05:43):

<laugh> certainly not my mom yet, but I didn’t know, you know, when I went into it, you’re right, I’m, I’m interested in a lot of different things and, uh, going into it, it was just sort of, you know, 15 of my own deepest questions about the interplay of nature and nurture and athleticism that had lodged in my head, either from my own experience as an athlete or from watching or, or talking to other athletes. Uh, so it, it, I wasn’t prepared to, to learn that there is many kind of, uh, physiology nerds out there as me <laugh>, I guess.

Brad (06:14):

Yeah, that’s great. And you really, you went really deep into it and examined some of these notions that we’ve long held as conventional wisdom we’ll say, that are pretty flawed and, uh, misconstrued. And you really went, you went at it in the book and you, you pulled no punches. And rather than just offering an opinion, you came out and said, look, here’s the research. Here’s what’s going on. And that’s what I think turned a lot of heads and, and got this book so much attention. And I highly recommend, uh, listeners read it, but even if not, you can search in your, um, podcast world for some great shows that you’ve already done that have talked about the book in detail. So I thought today we would just like kind of jump a little bit to some fun specific topics and get into a little more detail and hear hearing from you about how those things started and, and where the road took you.

Dave (07:07):

Sounds good.

Brad (07:09):

Yeah. So one of ’em is this 10,000 hour rule that has become it exploded into, um, public con consciousness and popularity, and you hear people dropping this sound bite all over the place. And for those of you unfamiliar with that, it’s the concept that if you put in enough time into anything, you’ll become a master. And oh, Malcolm Gladwell popularized it in one of his books and it’s just taken off and run with it. But you had a little bit of a different take and got into some research. So tell us, tell us where you stand on that one.

Dave (07:44):

Yeah, so this idea that that specifically sort of, there’s no such thing as an inate talent and 10,000 hours of practice is both necessary and sufficient to make anyone an expert in anything. I wasn’t all that, uh, familiar with it, to be honest when I started out it. And, but as I started reading through, uh, skill acquisition literature and science and sports psychology and things like that, it was ubiquitous. Like, it, it was everywhere, not just in popular media, because I also heard my colleagues at Sports Illustrated referencing it a lot, but it was really all over the research agenda. And, you know, I started to examine it. You know, at first I said, well, may, maybe this is true. You know, maybe all these things that look like talent, are really just built up, accumulated practice. And, but then I, I went back to read sort of the primary source literature where it came from.

Dave (08:33):

The initial study that that blew up, the 10,000 hour rule was a study of 30 violinists at a world famous music academy. And the, the 10 best of them had practiced on average 10,000 hours by the age of 20. And those were the people who could go on to become international soloists. And that’s kind of where the 10,000 hour rule grew from then it was just sort of extrapolated without evidence to every other activity. And the problem was, didn’t even really apply to the violinist for a number of reasons. So first was, uh, these 30 violinists had already gained admission to a world famous music academy. So that’s like the cardinal sin, as statisticians would say, of a restriction of range problem. So basically 99.9% of humanity had already been lopped out of the subject sample. So it’s like if you wanted to do a study of what leads to basketball skill and for your sample of subjects you choose chose only NBA centers noticed they’d all practiced a lot and concluded, therefore that only practice got them where they are not practice plus being seven feet tall, right?

Dave (09:36):

Because you’ve restricted the range of heights. So first of all, it couldn’t make the conclusions that it was making, second of all 10,000 hours was just an average of individual differences. And in fact, almost none of the violinists did reach 10,000 hours. It was just an average because a couple people went way over. And so it’s sort of obscure the individual differences that actually show up in the study skill acquisition. A great, you know, and so I started just sort of looking through all the literature and you’d come across these studies like chess, which skill and chess has learned in a similar manner to perceptual motor skill in sports. Hmm. And it takes 11,053 hours on average to become an international master in chess. But some people have made it by 3000 hours and some people are still being tracked at 25,000 hours and they still haven’t made it <laugh>. So it turns out the average really doesn’t tell you anything about the real picture of skill acquisition and, and the differences between people.

Brad (10:28):

Yeah. We had Christopher Smith on the podcast a few months back, and he’s, um, gained fame as the world record holder in the wonderful sport of speed golf, of which I’m a big proponent of. Mm-hmm. <affirmative> and his whole, he’s also a teaching, teaching pro in Portland, Oregon. And his whole approach to learning golf and to helping amateur players get better is to get them playing unconsciously. And, you know, blowing the, um, the notion that you have to hit a bunch of balls in practice and that’s gonna translate to competitive success is a misnomer because when you’re hitting balls on the range and hitting the same shot over and over again, it doesn’t have any application to the intense competitive environment that you face on the golf course and the unique shot that you face one time and don’t have to chance to do it over again.

Brad (11:23):

And he references brain research where even it goes so far as different parts of the brain light up when you’re sitting there on the driving range or the putting green, making twenty 3-foot putts in a row. So getting back to that 10,000 hours thing, if you sat there on the practice putting green and hit putt after putt until you accumulated that much time and then teed up on the first hole in a tournament you find might find yourself shaking like a leaf and having none of those skills that came because they don’t transfer directly to competitive environment.

Dave (11:52):

Yeah, I think that’s absolutely right on a number of levels. I mean, you know, and, and for one, just doing that sort of repetitive over and over logging the hours kind of activity, I mean, in some ways is like people who go to a gym and lift the same weight the same number of times every day, like very quickly you’ll have some physiological adaptation and then you won’t anymore because you’ve adapted to that task. So doing it more might stop you from sliding backward, but it isn’t gonna improve you. And so a big, a big concept now in a lot of elite training is called practice variability. Ah. Um, which is not focusing in on just that one skill over and over and over. And in fact, when early skill learners do that a lot, they actually seem to plateau earlier than they should.

Dave (12:32):

They almost get like stuck in a certain type of rhythm. So I think we’re, you know, at a lot of the highest levels that thinking’s kind of being reversed in favor of varying almost as much as possible sometimes even with just sort of general athleticism outside the sport, the activities that are being done. I saw some videos of training for the Chinese diving team, which is, you know, despite being a smaller sport is the greatest sports dynasty in history mm-hmm. <affirmative>, um, and they’re doing, you know, they’ll practice fundamental dives, but then they’ll have people purposely do dives that like, could never be scored in a competition, just like goofy stuff. And they’ll have them doing, you know, other kind of motor skills like learning how to juggle and practicing like cup stacking while they’re doing their planks. And it’s all, it’s partly for keeping things fun, but also to, to vary up practice. Cuz it seems like people that just kind of put in those rote hours, it doesn’t prepare them for the kind of things they need to do in competition.

Brad (13:27):

Right. So maybe there’s an element of keeping it fun and exciting, um, as a, as a critical component to, you know, the divers diving day after day after day and getting stale not only in the body, but in the mind too, I suppose.

Dave (13:44):

Yeah. I mean, once you’ve done a task, you know, so think of when you learned to drive a car, when you first learned to drive a car, you, you sort of, you know, you probably had to think, oh right turn hand over hand, you know, whatever. And then pretty soon that, you know, move from the prefrontal cortex, your sort of higher conscious area, back to these more primitive areas where you can essentially do it without thinking, right? Like you can do it while putting your makeup on, assuming like something unexpected doesn’t happen, right? In which case will crash <laugh>. But you can basically do it without thinking. So now it’s not like by driving for more hours, you are progressing toward being a professional race car driver because you’re doing things that your brain has already adapted for, that it makes easy and that thus do not make you get better or move toward being a race car driver no matter how many hours you put in of this kind of, um, easy to do driving that you’ve already adapted to.

Brad (14:34):

Interesting. Okay. So let’s say you do have a specific goal, like you want to you wanna break two minutes into the 800 mm-hmm. <affirmative>, and that’s a pretty, um, straightforward endeavor. Mm-hmm. <affirmative>, you have to get in pretty darn good shape and you gotta run a couple laps around the track. Mm-hmm. <affirmative>, um, where would it come in to have some practice variability?

Dave (14:55):

Yeah, so I was, I was, uh, an 800 runner myself.

Brad (14:58):

I know. Um, and, uh, So I’m trying to beat your time here. I’m, I’m training for it right now. I’m gonna need like five years.

Dave (15:04):

Gotcha. Um, and the, you know, practice variability actually turned out to be really important for me. When I first started doing it. I saw people putting in a lot of mileage. And so I started putting in mileage, just, you know, working up to more and more and more mileage. Got up to probably about 90 miles a week of training and it simply did not work for me. And then when I went back to varying things up to actually mixing in some kind of cross training, even a little swimming hill running, biometrics and intervals of different lengths, you know, sometimes even intervals that I wouldn’t even know until the coach told me we were about to do them. That worked for me like rocket fuel. And you know, that’s a similar thing I saw actually in Jamaica when I was watching runners train theirs the, one of the, probably the most famous track club there, which would’ve, you know, it’s like 20 people and it would’ve finished eighth.

Dave (15:55):

as the country in the last Olympics. Um, <laugh> was, they use a grass track. Uh, the coach there purposely. And I asked the runners, how long is the track? Cause it didn’t look like the typical 400 meters. And they didn’t even know. They were like, I think it’s 320, 330. And so the coach would just, you know, they, they couldn’t kind of guess exactly what their workouts here. You’d say like, you know, I want you to run from here to here or two laps around and stop here, or whatever. And they didn’t even know exactly the distance that it was. He was just always, always varying things up and, and purposely wouldn’t tell them the workout until they were right about the start. So they also had to kind of build in some of that mental flexibility. I think

Brad (16:30):

That’s great. It’s so important for athletes of all levels, even the, the casual or the amateur enthusiast to, to realize that it doesn’t have to be rote and regimented and, and so repetitive. So we have this concept of practice variability that’s taking the place of that, uh, misnomer that it’s all about volume, the 10,000 hours. But if it’s not about the 10,000 hours, let’s talk about the high jumpers from the book. Cuz that was my <laugh> that was my favorite chapter, another favorite sport of mine. But it was such a dramatic example of the place that genetics plays in high level athletics.

Dave (17:12):

Yeah. So this was this, uh, story in this second chapter that I call The Tale of Two High Jumpers. And one of those high jumpers is a guy named Stephan Holm a Swedish guy who became obsessed with high jump from about the age of five <laugh>. Um, you know, and was coached by his father who didn’t really know anything about High Jump, just was kind of a personal mentor. And, you know, Stephan was good early on, but he wasn’t great. You know, you wouldn’t have picked him out as any kind of prodigy or anything like that. And High Jump seems so much like something you either got it or you don’t. Right. And so you wouldn’t think of much of a guy who’s just good, um, not great, but through his training, I mean, Stephan became obsessed with HighJump and he improved one centimeter a year for 20 straight years until he won the Olympic Gold Medal in 2004.

Dave (17:56):

And he’s only about 510, 511, you know, cleared a bar, not much under eight feet <laugh>. Um, so he, he tied the record for the highest clearance over zone head. Yeah. Um, and he was, it’s funny cuz he has all these traits that like we idealize in competitive athletes. He’s, he’s super competitive. When I first talked to him, he said he didn’t have a girlfriend because High Jump was his girlfriend. He couldn’t cheat on her.

Brad (18:15):

Wow.

Dave (18:16):

And then, you know, the last time he actually has a young son now, um, and the kid’s name is Melwin, that’s not a typical Swedish name, but his wife liked the name Melvin and Ste insisted to win, be part of the kid’s name <laugh>. Right. So this is the guy you’re talking about here focused? Yep. Just a little. And then, and, and actually I think he has a bit of an obsessive personality cuz now that he’s, he’s locked his high jump equipment away, he’s become obsessed with Legos <laugh>. Wow. So I think he, he throws himself into whatever he does,

Brad (18:47):

New hobby.

Dave (18:47):

But in 2007 at the World Championships, he came up against a guy that nobody had really heard of. A guy named Donald Thomas. It’s actually funny if you watch the intros on YouTube to that event, the announcers say something like, and Stephan Home the favorite. And Donald Thomas, very much an unknown quantity, <laugh>. Um, and Donald had been a student at a small college in Missouri talking trash at lunch. And the best high jumper from the track team who held the school record, uh, at six eight overheard him and said, you know, you don’t even know what it’s like to be an athlete in real competition. You wouldn’t clear a bar of six six. And Donald says, well, yes, I would, you know, goes home, gets his sneakers. And this guy, this other guy, Carlos, sets a bar at six six and Donald clears it in a couple steps.

Dave (19:30):

And so he, they keep going up until Donald clears seven feet, never having jumped before. At which point Carlos thinks he’s gonna hurt himself, you know, takes him over to the coach. As coach, we have a seven foot high jumper <laugh> coach first doesn’t believe it, then picks up the phone, calls the next meet and begs for a late entry. So Donald’s there, you know, he doesn’t even have a team uniform yet. Clears about seven, five and a half, sets a field house record. Turns Pro pretty soon. And with eight months of training faces Stephan Holm in the World championships and in fact beats Stephan home in the world championships. So records the highest center of mass jump ever. But Donald’s form was so bad. It’s like he looks like he’s like riding an invisible deck chair. You know, he’s like sitting up. Well, he’s going through the air

Brad (20:07):

Looking at the bar while he clears it.

Dave (20:09):

Yeah, exactly. And putting his arms behind him. Cause he is not used to falling backwards. So he wins the world championship. I mean, I interviewed him after this, he says, I was like, well, what do you think about High Jump? Oh, kind of boring <laugh>, which is not something you hear from a typical world champion. Right? And he seems to contradict the 10,000 hours from both directions because he entered on top now he’s been a pro for over seven years and hasn’t improved one centimeter. So he started at the top and hasn’t gotten any better, you know, and part of his success turns out is the fact that he has this incredibly long Achilles tendon, which is basically like a spring in the back of your leg that he was born with. Whereas Stephan, through his training, actually hardened that spring over time. And of course, a spring can store a lot of energy by being either really stiff or really long. So there are two guys, you know, Stephan estimated his lifetime total at 20,000 hours and Donald was pretty close to zero. So like they average 10,000 hours.

Brad (20:58):

Hey, they validate the theory. All right. Exactly.

Dave (21:00):

It doesn’t tell you anything about the reality of human performance.

Brad (21:05):

So this one thing I’m thinking about, I’ve thought about a lot, uh, in, in pondering these concepts is you have this, this physical genetic gifts, which are so obvious you’re watching the NBA and these guys of course have worked hard and all that, but they’re also, um, you know, one in a million genetic freaks just like Donald Thomas, just like everybody on the start line for the Olympic a hundred meters mm-hmm. <affirmative>. Um, and then when you’re talking about Stephan Holm, or one of my favorite examples from triathlon, Mike Pigg, um, he had this, these genetic particulars, you could say to the extent that he became obsessed with high jump and, and chose high jump over girlfriends and all that. And that’s, these are genetic attributes that are very rare and are well adapted to becoming an elite performer. And in Pigg’s case, if you or the listeners haven’t heard of him, he was a guy who was always characterized as not very talented natural athlete, but he works harder than anybody else. And it’s sort of an unfair characterization. But when you think about, um, his mindset and his desire to train that was so incredibly strong every single day throughout his career, I feel like those are genetic gifts that are right there on a par with the physical stuff.

Dave (22:25):

I completely agree with you. And in fact, the, there were a number, some of my own intuitions and guesses, um, about nature, nurture of athleticism were overturned in the reporting of the book. And probably the most surprising aspect to me was the chapter where I talked about sort of compulsion to train. And so I, I knew very well from following the physiology that things like our brain’s dopamine system, you know, the chemical system involved in your sense of pleasure and reward, whether that’s for eating or having sex or doing drugs or exercising or whatever, I knew that that responded to things like our physical activity making some people, you know, want to, want to do them reinforce what they did. And others maybe not as much. But I didn’t know at all that that scientists who study that area know the reverse is true too.

Dave (23:15):

That actually differences in our dopamine system from the get-go can cause some people to have a compulsive drive to train where other people, it’s really, really difficult, uh, for them. They don’t feel that same sense of reward, you know, in, in, in being physically active every day. And it’s incredible to, to read some of the mouse models that have been made to simulate human dopamine systems because you can breed really easily mice to be like crazy runners just wanting to run like totally crazy just by taking a group and separating the ones, ones that run a little more voluntarily from the ones that run a little less in breeding those groups in a couple generations, you have these ones that are like total slobs, <laugh> and others that are just manic runners. And their dopamine system looks like some ultra endurance athletes and humans.

Dave (24:00):

And you can actually give them drugs. Like you can give them drugs and take that away from them. You know, drugs like some ADHD drugs. I mean, ADHD includes a compulsive drive to move around and you can give this certain drug and, and then satisfy the dopamine system so it doesn’t feel the need to do that anymore. And it’s, it’s kind of amazing. So those mice literally become crack heads for exercise. Wow. And you can satisfy it by letting them run or by, by drugging them. Um, and I just thought that was fascinating. I mean, one of my favorite interviews was with Pam Reid, the legendary ultra-marathon runner who when I interviewed her, she had just in her mid fifties done competed in Ironman Triathlon Nationals, and it was in New York actually. Mm-hmm. <affirmative>. And she qualified for worlds in her mid fifties.

Dave (24:41):

And her flight out of LaGuardia Airport was delayed because of course it’s LaGuardia airport, everything’s delayed. And when I was talking to her, she was so antsy. This is a day after she, she qualified from National Ironman championships that she had put her bags away and was running laps around the parking structure, like 200 meter laps around the parking structure while I was interviewing <laugh> because she’s so disliked sitting still. Right. I mean, obviously that’s a very extreme example. Um, but, you know, some people, I think that kind of compulsive drive to train comes easily to them. And it doesn’t mean that other people can’t accomplish it, but they might have to work on their environment a heck of a lot harder. It might not come to them as easily.

Brad (25:20):

Yeah. I guess, uh, would involve finding something that you enjoy so much like Stefan Hol did, or like Pam Reid does with her ultra endeavors and, you know, locking into that, that’s what we, you know, that’s, that’s the what parents wish for their children and all those kind of things that you, you develop that incredible passion where you just, you just go for it.

Dave (25:40):

Absolutely. You know, and I think, and I think for most people there is something like that. It’s just a rare exception when that thing happens to be what they do for a living. Also <laugh>. Um, so I think most people can find that it’s just, it’s just difficult for it to be their living. But for some people, I think when it comes to, to actual training or exercise, sometimes something as simple as a training group, you know, can be a, uh, an environmental manipulation that makes it easier for you to get up and go do that work. I mean, I look at the guys that I trained with in college and some of them post competitive career, still compete like crazy and trained like crazy and others went cold turkey and don’t train at all. So clearly the environment we were in, um, caused some guys to actually train less and some guys would train a lot more.

Brad (26:26):

Well, I wonder what the secret is for, uh, the longevity aspect if they’re, they’re, they’re finding they’re in a new environment, obviously, but something’s still clicking for them.

Dave (26:37):

Yeah, I mean, one of the guys I wrote about in the book was one of my training partners, and he kind of stagnated in college after coming in as a very big recruit mm-hmm. <affirmative>. Um, and, you know, I think there were differences in his, my ability to, to respond to the training we were being given. At the same time, I think they, instead of kind of just saying, okay, well he’s stagnating, that’s, that, the coaches should have introduced practice variability there because he had stopped improving. But once he got out of college and was in charge of himself again, he started mixing it up and trying different things and, and actually made, uh, the world championship in the duathlon. So he was clearly not done. I think he just needed some, some training changes.

Brad (27:16):

Yeah. I think people become afraid to go against, you know, the traditional approach to training. The coaches are afraid to mix things up. I mean, some of our best workouts in high school running group was when, you know, we’d just go to the beach like thinking it was gonna be an off day or something and we’d make up little follow the leader or chase games into the water and running down the beach and by the time you’re done, it was a better workout than if you’d stayed at the track and banged out the usual interval workout that everybody dreaded. So, I think for the, the average listener out there who’s got fitness and athletic goals, it’s absolutely okay to, you know, um, try all kinds of different assorted things that work toward enjoying it and having a passion for it

Dave (28:04):

Completely. And I mean, that is form of practice variability cuz you know, you’ll maybe when you were doing that, your hips were a little sore the next day and you realized those weren’t muscles that you were, if you ever played like beach football or anything that, that you weren’t working when you were on the track. And actually Pam Reid herself, you know, who’s one bad water was one, like very prominent, uh, ultra endurance events is a huge proponent of like using whatever few minutes you have at a gap in your day as, as using that for some fitness. However you’re gonna do it. Like not having to say, okay, well these, this is my hour or two hour window after work and I either make it or I don’t. But using the times you have to, to create things, you know, it doesn’t, doesn’t have to be perfect to get started on on doing some fitness activities.

Brad (28:47):

Yeah. Good example. No, no, no need for excuses. And when you mentioned bad water, I’ll just clarify that. That’s this crazy 146 mile run across Death Valley ending up in the Sierra Mountains and she won the whole thing, right? She beat all the men one time.

Dave (29:04):

Uh, I think she finished or she seemed like third overall or

Brad (29:06):

Something. She second overall. Yeah. Yeah. Second or third overall. Unbelievable. Yeah.

Dave (29:10):

She once ran, she ran 390 laps around like a mile loop in Queens without sleep. I mean, she’s obviously quite an outlier and it’s pretty amazing <laugh>

Brad (29:21):

But interesting dopamine system going on there. Yeah,

Dave (29:24):

For sure. She actually is so curious about it that she’ll like try to follow up sometimes with what’s going on with like these mouse models and journals cuz she’s, she’s also very curious about herself and realizes <laugh> she’s different than the normal person.

Brad (29:38):

Oh, that’s great. Um, you know, one other thing you did really well in the book was to refute some of this latent prejudice that we have toward successful athletes. And we turn on the Olympics and we watched the runners from Jamaica kick butt on everybody, including America where they’re outnumbered in population by what, a hundred to one or something. And we make this reference in the back of our mind that these guys are God’s gift and that’s why they’re, that’s why they’re winning the medals is cuz they were born with that talent. And it’s not so simple, is it?

Dave (30:17):

No, and I mean, like you said before, anyone who lines up at the Olympic 100 meters, right? Like they’re, they’re not normal <laugh>. And we know from studies of tens of thousands of athletes that slow kids never become fast adults. Right. <laugh> like, you’re gonna to the olympic hundred meters. Like you, you have to have some speed. But I mean, even think about someone like a Usain Bolt. If he’s born in the United States, there is, hi, his favorite sports were soccer and cricket <laugh>. And if he’s born in the United States, he’s six four. When he is 15 years old with blinding speed, there is no way he ends up as a track athlete. Right? He’s a wide receiver. Yeah. Or he’s a basketball player or whatever. So I guarantee there are others of him out there. But what you have in Jamaica is you have this kind of amazing talent spotting system for high school track.

Dave (31:03):

High school track is all rage there. It’s not, not pro track. And people act like kind of how college football boosters do here. They see someone from their parish, they, oh, we don’t wanna let this kid get away. We have to, you know, entice them to our school and so on and so forth. And it becomes this incredible sort of, you know, almost like the feeling of like a pro circuit for the high school kids and then they have their meet at the end of the year that’s 35,000 people packed stands and it’s something that everybody wants to be a part of. So I think they’ve sort of created this culture that makes it very, very hard for a talented sprinters to slip through the cracks even, even if they try, like you saying bolt, you know. So I think they’re really making the most of what they have and also have added on top of that in aversion to over racing Uhhuh <affirmative>. Um, but I think in some cases the college system here, uh, can be prone to for sprinters. Um, so I think they’ve have confidence in their methods enough not to overtrain,

Brad (31:56):

Yeah, yeah. You, you can’t say enough about that because so many athletes fall short of their potential due to this regimented high volume mentality, the 10,000 hour mentality toward training. And you pointed out, or I guess you quoted Usain from his own book saying that he was lazy and he didn’t train as hard as his teammates and um, you kind of highlighted that as maybe that’s not so bad.

Dave (32:23):

Yeah, I mean, well I went to see some of his practice. He spent like more time trying to balance a traffic cone on his head than he did, you know, like doing anything else but the, you know, but one, he did spend a lot of time doing technical stuff on starts like just practicing starts. And if you’ll notice, if you’ve kind of slow mo him in, in a start, he does this thing that’s now being called a Jamaican tow drag where he actually drags his, his back foot along the ground when he takes the first step. And the idea is to keep a very acute angle, um, between your, your leg and the tracks. You don’t wanna pick it up much and try to step out and the Jamaicans do that really well. So he was just practicing that over and over and over and over.

Dave (33:00):

So he is really, you know, I don’t think it’s, I I think that’s part of the reason why he’s a better starter than any guy his height has ever been before. Um, but also I think part of his, you know, he won World Juniors when he was like 15 years old and that’s an under 19 competition <laugh>. So that’s incredible cuz a 15 year old is usually a boy among men in that kind of competition. And so people said, wow, you know, if we can really get this guy to actually train, he’ll be great. And so a couple years later, you know, he’s, he’s training harder and he’s injured all the time. We don’t hear from him for a couple years. So then he switches coaches to a coach who I think, you know, Usain Bolt might call it laziness, but I think part of it is he’s listening to his body and he knows, you know, that when he trained a certain way he was injured all the time. And so he laughs it off as laziness, but I really think some of it is him knowing himself and having a coach who allows him to act on that.

Brad (33:52):

Well, something’s working for him and he also seems to be very patient and knowing how to peak at the right time. Cuz here he is finally putting up some fast times after he’s been struggling for maybe 18 months and oh, we’re just in time for the world championships coming up. Yeah,

Dave (34:07):

Yeah. You know, and I think that’s, so one of his training partners, Johan Blake, um, who was the silver medalist in the last Olympics is an, is an animal in training. He trains really hard and Blake really hits the weight room hard. And speaking of peaking, you know, so there’s this interesting phenomenon where explosive weight or sprint training actually causes some of your type two B or super fast twitch muscle fibers to convert to type two A, which is fast twitch but not as fast. Mm-hmm. <affirmative>. And you think it would be the opposite, but that’s what happens. And then when you stop the lifting or sprint training, it comes back up to baseline and actually overshoots before coming down to baseline. So there’s a small period a little bit after you stop the sprint and weight training where you will temporarily be as explosive as you’ll ever be again. And I think Bolt gets out of the weight room early enough to capitalize on that. Whereas you see Blake, when he was, you know, when he wasn’t injured, he was running as fastest race as always like a month after worlds or the Olympic Olympics. And I think that’s because he was coming outta the weight room too late to capitalize on that, that little physiological glitch or whatever you want to call

Brad (35:09):

It. Wow. Yeah. Adaptation something. Yeah. Yeah. Um, I think the endurance athletes have found, I’ve had a few anecdotes myself where you go out and do a, a really long training day and then the next day you think that you’re gonna be tired, but you actually, you know, deliver peak performance just cuz whatever the blood volume’s higher the stress hormones are circulating. So there’s some tweaks here and there, but I think a lot of this discussion has led to sort of a, um, a conclusion or a summary at this point that individualization is, is the main deal here. There’s no secrets or templates really. Yeah.

Dave (35:46):

And I think in, and that goes back to something you were mentioning earlier, right? Is like, you know, mixing up practice and, and I think a lot of the reason why some athletes like don’t improve when they get to college is, is it’s efficient for a coach basically to have these sort of cookie cutter programs and throw everyone into them and just take through the people who survive because they don’t actually need every runner, right?

Brad (36:06):

Mm-hmm. <affirmative>, right?

Dave (36:07):

But, but I don’t think it’s like a surprise that individualization is actually the best way to go. You know, if we look at s may, you know, some of the most important findings that have come out of medical genetics since the sequencing of the human genome, it’s to find that, you know, because of differences in your gene involved in acetaminophen metabolism from mine, you might need three Tylenol. Well, to get the effect that I only need one, or you might not metabolize it at all, so you might not get any effect from it. And it’s looking very, very similar for the medicine of any type of training, which is that people’s genetic differences mediate how much effect they’ll get and, and what’s the best training plan for them. So I really think we should all view our training plans. Like there’s certain fundamental things that, that everyone has to do, but that as we get better, we should view our training plans as kind of this exploration of self where you’re, you know, kind of working your way, whether it’s directly or take a step in the wrong direction, then a step in the right direction toward the specific program that is best for your completely inimitable physiology.

Brad (37:10):

So that means a lot of trial and error, a lot of record keeping and observing and maybe, you know, being more open-minded rather than just opening up a book or, or you know, blindly following the, um, the template of the program that you’re participating in if you’re a, a young runner or, or what have you.

Dave (37:29):

Yeah, I mean I think there’s a reason why exercise fads and diet fads and so on rotate so much. And I think part of it is because they never work for everybody, even if everybody’s doing the same thing. You know, that’s what we’re seeing in these genetics training studies is two people doing the exact same training can have like a hundred percent difference in their, in their improvement or their trainability, right? And so I do think you have to be more open-minded, you know, I mean, I guess you can do certain things to get some clues if you’re crazy like me and wanna get like muscle biopsies and stuff. But that’s still not gonna tell you a lot of what you want to know. So I think being open-minded, paying attention when something’s not working as well for you as it is for your training partner, you know, and I know nobody wants to feel like they’re trial and erroring because it sounds like it’s sort of wasting time. But I, but I think it’s sort of essential if you’re gonna end up finding the program that’s best for you and, and, and sort of keeping, uh, you know, keeping training diaries sort of thing so you can, I think you start to helps you get a sense of what is actually working for you and what works with you, works for you from season to season.

Brad (38:28):

Excellent. Let’s switch gears a little bit cuz you just wrote a very interesting and lengthy article on a topic that’s been on the minds of a lot of sports fans in recent years, and that’s doping performance enhancing drugs and sports. Uh, but first tell us about the forum where this article appeared ProPublica, and how’d you get into that? Yeah,

Dave (38:49):

So ProPublica, where I work now is, uh, uh, I used to be at Sports Illustrated is a nonprofit, um, journalism started up maybe five or six years ago by the guy who was running the Wall Street Journal and the investigative editor of the New York Times with the idea being just to house reporters who work on long projects, you know, most of us like working with data to, um, and you know, we then place those, those projects with other media. We partner with other media. So in this case I was partnered with the BBC and we produced a film, a three part film about doping. And then I also wrote a companion article about our investigation, um, into, uh, you know, the team coached by the Nike sponsored team, coached by Alberto Salazar, who’s probably the most prominent track coach in the world. Um, and looking at, uh, you know, allegations of sort of misuse of medications for performance advantage allegations by former athletes of their doping and, you know, sort of skirting the intent of rules or, or actually just breaking the rules basically.

Brad (40:00):

Yeah, it was pretty, it’s pretty tricky stuff cuz it wasn’t as cut and dried as, um, uh, you know, Lance Armstrong being right. People confessing that, um, you know, there’s needles all over the place and cycling, um, right. And so not to get, and little not to get too nuanced here, but you wrote this lengthy article, if you’re interested in this subject, definitely read it on ProPublica. And then, Salazar issued a pretty lengthy rebuttal and he did a, I’d say a, a fair job of covering his ass, but it also brought up even more questions and suspicions. And I just wonder, um, how, how you feel about the whole scene now after seeing your subject respond pretty aggressively.

Dave (40:42):

Yeah, I, I wish he would’ve, I mean, we sent him, you know, these like reams of questions a month, I think it was 27 days in advance of publication. We kind of wish that he would come on the, come on the film for the interview. Yeah, really. Um, but I’m still glad that he, that he put a, a detailed response out there and I think for the most part the response confirmed, except in one case he confirmed the facts that we alleged and disputed the interpretations of the people who worked with him. So, for example, yeah, he confirmed having tested testosterone gel on his sons in the Nike lab,

Brad (41:13):

<laugh>, whoops, could you repeat that? <laugh>, and of course made a, made a convenient excuse for that, that he was, he was testing to determine how, how easy it would be to sabotage one of his athletes by patting him on the shoulder and having a handful of cream

Dave (41:29):

<laugh>. Right. And I, and at the time when that sort of thing was alleged in relation to Justin Gatlin, he said that it was preposterous, you know, and I, I still want an answer about how testing it on your sons in the Nike lab would protect you from sabotage. So I still don’t understand that part. But, you know, maybe, maybe that that was the case, maybe that’s what he was doing, but even so I think that’s gonna, you know, could potentially be problematic for him. And, you know, he admitted to hiding like prescription painkillers and magazines and books to ship them overseas to avoid customs. And I think, you know, even though those prescription painkillers aren’t on the band list, you know, in some cases they’re going to people who don’t have prescriptions. And so I’m curious to see how UK athletics, I think they’re, they’re gonna make a determination on whether he is still gonna be a consultant to them soon.

Dave (42:21):

I’m curious to see how that plays out. But overall, I think what I’m glad occurred is that it seemed to open a conversation not about banned drugs, right? Like there’s a lot of conversation about that, but about how we should approach, um, medicine and medical exemptions when they may be being used for performance enhancement or for people who don’t otherwise under normal conditions need those medications. And I think that was an important discussion to open. And so that’s, that’s the part I’m most glad about your respective of, you know, the sort of specifics of of Alberto Salazar.

Brad (42:55):

Oh, sure. And it, it just, it also reveals what a gray area this is because you can go get a doctor to say, Hey, you’re thyroid screwed, you need this and you need this and you need this and be playing by the rules. But you know, the moral objections of, you know, all these things come into play and, um, you know, one of, one of the ideas that Mark Sisson and I have talked about on a previous podcast with Mark’s sort of frustrating experience presiding over the, um, anti-doping efforts of the sport of triathlon for many years, um, you know, one thing he suggested was, wait a sec, maybe we should just, you know, help these athletes legalize some of these performance enhancing agents so that they can preserve their health as best as possible. For example, if you’re riding the Tour de France, um, one of the most unhealthy things you can do to the human body, by the way, would it, would all the writers be better off if their hematocrit were pegged in the high forties so they could have maximum red blood cell oxygen carrying capacity during this, you know, physically destructive event.

Dave (44:01):

Yeah. And to be honest with you, speaking of that, I’m, I’m totally open to that discussion. And speaking of that hematocrit, you know, cuz because they’re not supposed to start, if their hematocrit’s over 50 proportion of their bloodstream, that’s red blood cells, right? And, and that’s claimed to be for their health reasons, but I don’t totally believe that. I think it’s an attempt to, you know, not have like a blatant doping case because there are athletes like in CrossCountry skiing who have had hematocrits way higher than that and they’re documented to have had those over time and be normal. You know, 50% is high, higher than that as the highest I’ve seen. Um, and you know, they’re not, they’re not dropping dead or anything like that. Um,

Brad (44:34):

Yeah. What was the, um, the red, red complexion guy from Finland that you went to visit that had all the metals from, um, yeah. From cross country and he was, he was determined to be a somewhat of a genetic, uh, freak with his incredibly high hematocrit?

Dave (44:50):

Yeah, I mean, he had, his hematocrit would get into the mid sixties <laugh> and he had a gene mutation that caused his receptor for the hormone EPO to, to over respond to the natural levels of his hormone and just like crank out red blood cells. Um, and no members of his family had that, some of members of his family had that. So he won seven Olympic medals. He won some races in, in at the Olympics and margins that have never been, uh, never been equaled since. And you know, like one of his nephews who has the condition was also an Olympic gold medalist in cross-country skiing. A niece was a world junior champion and people who didn’t have it in the family weren’t good, uh, racers. So they dealt just fine with this overabundance of red blood cells. But, but I do think you have a point, you know, I think, I think there’s some drugs, doping drugs that would be kind of hard for a sport to legalize because steroids, for example, are, are schedule three controlled substances in the United States.

Dave (45:43):

So it’s not the sports purview to to be allowed to kind of trump the law of the land, at least in the United States. Um, but others, I think there are things on the band list that are not performance enhancing and things that aren’t on the band list that are performance enhancing. And I don’t advocate taking the rules into your own hands because all sports are is just, you know, a contrivance with agreed take, agreed upon rules and add meaning <laugh>. But I certainly think there should be a more open discussion, uh, with multiple parties, including athletes giving feedback into, into how we should treat those substances. And the band list.

Brad (46:12):

We9ll, we’ll see what happens in the future. And speaking of that, what’s, what’s up with you? Are you, what are you working on a new book, new exciting articles? Where are you headed?

Dave (46:21):

Well, I’m working on some articles, but by nature of being investigative stuff, I guess I shouldn’t talk about it too much, but, um, books on like, on step like seven of 12 to recovery for my first book. So

Brad (46:32):

Yeah. Yeah.

Dave (46:32):

I’ve, again, you know, when I was finishing it, it was kind of reminded me of the 800, it’s like in the middle it was torture. And if at the end you think you did pretty well, you’re like, oh, that wasn’t so bad, maybe I’d do it again. Um, <laugh>. And so I’m, I’m getting toward where I’ve opened the, uh, the notebook again to start jotting down sort of possible book ideas and, and one I added an afterward, uh, to the paperback version of my book about specialization in youth sports and all the data piling up suggesting that actually starting with diversity, um, and going to specialization is, is the way to go for skill development, not just for, for health and, feel-good message. And I’ve kind of gotten interested in that inside and outside of sports, this idea of diversifying first before specializing since I think in most things in society, we’re moving towards specializing as quickly as possible. So that’s kind of an a broad idea that I’m thinking about now that I’d like to develop bigger project on.

Brad (47:24):

Oh boy. I mean, you could apply that to the world of academia because now with the technology and the economy changing so much, you know, in my generation, I’m an old guy, 50, you know, you’d go to college and most people’s focus was, what’s your major and what job are you going to get for your duration of your career after you graduate with that major? And you know, for example, I majored in economics, accounting emphasis, and my accounting career lasted 11 and a half weeks until I decided I hated it and wanted to be an athlete <laugh>. And so, that was sort of, you know, it didn’t play out as intended, but so many people, you know, they, they stayed with the same company for years and decades. And now I think today’s college student, it’s probably an entirely different future ahead. And maybe the specialization of education and learning some distinct skill might not be as valuable as just broadening, you know, staying broad for as long as possible.

Dave (48:24):

Yeah, I, I kind of agree, or at least I think that’s interesting. I don’t know what if there’s rigorous work on it says, but you know, whenever I see articles about Facebook is looking for philosophy majors and things like that, you know, it’s like the biggest problems, uh, around seem to be very much interdisciplinary problems. And even if they require specialists in certain areas, I think those, there’s more value on on specialists who have some facility working in thinking in other areas as well. So I’m kinda interested in that generally. I’m hoping there’s some rigorous research done on it.

Brad (48:56):

<laugh> Yeah. Really well, um, we will, we’ll have some research coming in now where you, you hear the talk about how, you know, India and China and their large populations are now training highly skilled students to come and, you know, take over some of the, um, the, the technical careers that, um, have long been, you know, a gravy train for, uh, American workers. Yeah. So we’ll see. We’ll have some research playing out in the next 20 years, huh? Yeah.

Dave (49:23):

Yeah.

Brad (49:24):

So, Dave Epstein, thank you so much for joining us, author of the Sports Gene. Definitely grab that book if you’re interested at all in the subject. It’s fascinating, extremely well researched and he’s been pounding the pavement, traveling all over, promoting this thing, and I think it’s still got a long life ahead of it. So keep up the great work and thanks for having, having the time to spend on the Primal Blueprint podcast.

Dave (49:46):

It’s my pleasure, and thanks for being persistent and patient. I’m glad it worked.

Brad (49:53):

All right, Dave Epstein. Thanks for listening. This is your host, Brad Kearns.

Brad (49:56):

Hey listeners. Brad Kearns here with a commercial message. I know maybe not your favorite part of the show, but this is different because I am excited to tell you about my absolute favorite thing to eat on the planet. And it’s Thompson River Ranch, ultra high grade, long grass-fed American Wagu beef. Check them out at thompsonriverranch.com. You’ve heard about how important grass-fed is. You’ve looked around the stores, it seems kind of expensive. Don’t know where to get it. Thompson River Ranch takes care of everything now because you can order direct off their website, ship to your door with the most delicious beef that you’ll ever taste in your life. My favorite is the ground beef. I’ll order 60 or 80 pounds of their convenient small packages for cooking. My friends, my neighbors, everyone’s in on it.

Brad (50:38):

Once you taste it, take one bite, it’ll change your life because you’ve never tasted anything so good. Cook it plain in a pan, no sauces, and just do the taste test. And Thompson River Ranch will blow you away. So for podcast listeners, they have a special offer. Just enter the word podcast on their website in the discount field, and you’ll get a 20% discount. The least you can do is try one shipment. And I’m telling you, the short ribs, they were the biggest hit ever at PrimalCon, the ground beef, you can’t go wrong and you’ll be eating some of the most nutritious, delicious, and humanely raised animals that you’ll find anywhere on this planet. Go to Thompson River Ranch.com, read more about their mission statement and the quality, and also shop for all the different kinds of meat that you’ll enjoy at home Ship direct to your door in cold packing.

Brad (51:23):

I hope you enjoy this episode and encourage you to check out the Primal Endurance Mastery course at primalendurance.fit. This is the ultimate online educational experience where you can learn from the world’s great coaches and trainers, diet, peak performance and recovery experts, as well as lengthy one-on-one interviews from several of the greatest endurance athletes of all time, not published anywhere else. It’s a major educational experience with hundreds of videos, but you can get free access to a minicourse with an ebook summary of the Primal Endurance Approach and nine step-by-step videos on how to become a primal endurance athlete. This mini course will help you develop a strong, basic understanding of this all-encompassing approach to endurance training that includes primal aligned eating to escape carbohydrate dependency and enhanced fat metabolism. Building an aerobic base with comfortably paced-workouts, strategically introducing high intensity strength and sprint workouts, emphasizing rest, recovery, and annual periodization. And finally, cultivating an intuitive approach to training. Instead of the usual robotic approach of fixed weekly workout schedules, just head over to Primal endurance.fit and learn all about the course and how we can help you go faster and preserve your health while you’re at it.